Blog | July 2019

Reflections on the ‘Grey is the New Pink: Moments of Ageing’ Exhibition

by Megha Amrith and Dora Sampaio

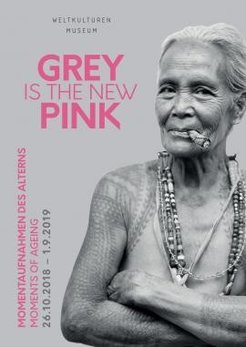

On a Tuesday afternoon in July, the Weltkulturen Museum along the banks of the river Main in Frankfurt offered a quiet, slow and reflective space to visit the ‘Grey is the New Pink: Moments of Ageing’ exhibition. It had been almost a year since we first heard about the exhibition and we became curious and fascinated by its evocative promotional material. Yes, the title and hashtag are gimmicky, yet fun, and the image on the main poster we found to be bold and provocative, ready to unsettle some of the dominant images depicting ‘ageing’ (in ways that are largely medicalized, or depicting passivity and decline) that one typically finds. All we could hope for was that the exhibition would not exoticize, dogmatically categorize or essentialize ageing experiences. It did not. Indeed, as with things you look forward to, there is always the risk of feeling underwhelmed, but ‘Grey is the New Pink’ did not disappoint.

The exhibition notes that ‘there is no universally valid definition of when “old age” starts’. So, who is old – where and when?’ It ‘presents diverse ideas and models of “age(ing)” from the perspective of cultural studies and the visual arts, as well as personal and individual experience’. In the multiple ‘moments of ageing’ portrayed, the exhibition tells a fundamentally human story of ageing across the world: of intimacy and companionship, of people with rich life histories, of moments in solitude and introspection, and of the different materialities that matter to people. It also tells a story of the diversity of ageing experiences that comes across through the many contributions and self-representations – displayed in the main halls of the museum - that people sent in from their personal archives of family albums and smartphone images, responding to the ‘call for contributions’ that the curators put out. What was most refreshing here, was the culturally nuanced way that ‘moments of ageing’ were presented without a Eurocentric narrative of ‘our’ or ‘other’ way(s) of ageing. It avoided static state-bound constructions of ageing experiences (such as ‘ageing in Germany’, ‘ageing in the Philippines’, ‘ageing in Kenya’) that policy work and studies of ageing can sometimes reproduce. At the same time, we thought that it was interesting to think what this exhibition might do for visitors in the ageing society of Germany, to unsettle assumptions about ageing that people might hold as given and to stimulate, provoke, or interpret with multiple perspectives.

In its diversity and originality, the exhibition challenges naturalized age categories, heteronormative views of ageing and relationships later in life, and reflects upon ‘ageing without borders’, of whatever kind they might be. The power of the images and objects displayed, guide the visitor through the lives and experiences of differently-situated individuals and communities without the need for excessive written interpretations. To offer a few examples: in one series of photographs, an artist captures the life of an older woman without showing her face, her story is instead told through images of interior spaces and objects of home and home-making.

In another artistic installation, we see the cultural relevance of tattoos as bodily markers of age, ageing and intergenerational continuity. There is also a series of photographs and narratives on the intersections of ageing, gender and sexuality that we found poignant. These powerful moments of ageing prompt thoughts about life and death, cultural legacies and they hint at how global intersections and forms of power – colonial occupations, structural discrimination, the commodification of culture and tourism - shape everyday livelihoods and experiences over the life course. In our view, such an approach to age and ageing in articulation with social change and inequality is not only welcome but necessary. Yet, we also felt that more could have been depicted as regards inequality and vulnerability in older age. While an optimistic outlook on ageing shines through this exhibition, which we found distinctive, we could not help but wonder about the less ‘shiny’ and positive aspects of ageing and how that could be captured artistically without falling into stereotypes.

The exhibition also makes use of different forms of media – photographs, written narratives, a book corner, short videos, objects, poems and proverbs – where there is a representation of artists from different parts of the world. In observing and listening to these stories, we were touched, they made us laugh, they evoked intensely personal and shared experiences of growing older in all its ambivalence.

Here we highlight the #hipstergrandpa Instagram accounts (check them out), for joyfully overturning assumptions about ‘naturalized’ conventions about age, aesthetics, identity and lifestyle behaviours. All throughout, it is clear the value of a sharp ethnographic eye that the curator, Alice Pawlik, brings to the framing of the whole exhibition.

Looking back at our visit, we were left wishing to hear more about ageing in its relationality. How do the stories presented interact in such a connected and mobile world? How do these stories relate to family and younger generations and what other stories could be told? While the images and objects presented were certainty telling and fascinating, some of these broader socio-political framings we thought were a little too implicit or hidden (though perhaps that was the intention of the curator). The most puzzling section of the exhibition for us was the part on ‘blue zones’ (zones in different parts of the world that demonstrate ‘optimal lifestyles of longevity’) together with the TED talk on ‘How to live to be 100+’. We found the premise of ‘how to live longer’ reflective of a normative discourse on striving for ‘ideal ageing’, on following ‘ideal’ or ‘desired’ lifestyles (what to eat, how to exercise, how to live) designed for more ‘successful’ or ‘better’ ageing lives. This, we felt, ought to have been presented as an object of ethnographic inquiry in itself – i.e. who defines what ‘successful ageing’ is? (see Lamb, 2017 for a critique of Successful Ageing as a Contemporary Obsession). There was more scope for a critical and open discussion on what such framings obscure: for instance, that being optimistic about older age does not equate to a universal presumption of wanting to ‘live to be 100+’, or that not living to be 100+ does not reflect individual failures (here again, the question of intersectional inequality returns).

All in all, we found this exhibition to be an effective and greatly captivating way of sharing research and engaging with the wider public. It shows the importance (urgency even) of taking academic work outside the conventional academic settings and generating new spaces of dialogue, introspection, and creativity. We hope this exhibition has reached and continues to reach many people. ‘Grey is the New Pink: Moments of Ageing’ is provocative and a great example of how to make questions of ageing and older age interesting, relevant and accessible to the public, regardless of their age.

‘Grey is the New Pink: Moments of Ageing’ is in exhibition at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt until September 1, 2019.

More information here: https://www.weltkulturenmuseum.de/en/content/grey-new-pink-moments-ageing