Blog | June 2021, Sidecar

Pavelić’s Ghost

by Jeremy F. Walton

This blog was originally published on 3 June 2021 in Sidecar.

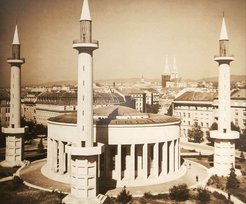

Like all holidays, the advent of Ramadan unleashes a social media storm of congratulatory memes. Friends, family, and distant acquaintances share photographs of mosques and stylized images of the crescent-and-star superimposed with a snippet of text, ‘Ramadan Mubarak’ or ‘Ramadan Kareem’ – wishes for a bountiful holy month. My twitter feed brimmed with such greetings on the first morning of Ramadan, but one in particular caught my eye, a retweet of Jusuf Nurkić, the Bosnian basketballer who plays centre for the Portland Trailblazers in the National Basketball Association. Nurkić’s message was brief: the hashtag #ramadankareem, three emojis – a crescent moon, a heart, and a pair of hands expressing gratitude or piety – and a caption for the accompanying photograph: ‘Zagreb. 1944 Croatia’. The black-and-white image that Nurkić tweeted depicted a rotunda surrounded by three towering minarets. The sinister political context captured by the photograph was implicit, but the flood of responses to the tweet indicated that it was not lost on Nurkić’s followers. He had posted a picture from a notorious episode in Zagreb’s history: the conversion of a famous art pavilion into a mosque by the Nazi comprador government of the Independent State of Croatia and its leader, Ante Pavelić.

Along with Ferenc Szálasi in Hungary, Ion Antonescu in Romania, and Jozef Tiso in Slovakia, Pavelić was a quisling dictator who rose to power on Hitler and Mussolini’s coattails. His Ustaša Movement seized power in 1941 following the Axis attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In short order, they set about cleansing ‘Greater Croatia’ – a region that included most of Bosnia and parts of Serbia’s Vojvodina region, as well as Croatia – of centuries of linguistic, religious and ethnic plurality. Pavelić’s most gruesome legacy was the Jasenovac concentration camp, a marshy abattoir on the floodplains of Slavonia where some 100,000 Jews, Roma, Serbs and anti-fascists were murdered between 1941 and 1945. The Ustaša ambition to Croat ethnic purity was assimilatory as well as genocidal. Drawing on the marginal theories of the 19th Century proto-nationalist Ante Starčević, Pavelić and his cohorts argued that Bosniaks were religiously but not ethnically distinct. In other words, the Ustaše considered Bosniaks to be Muslim – rather than Catholic – Croats, thereby erasing all historically- or culturally-rooted claims to Bosniak distinction. As ostensible Croats, Muslims were desirable components of the Ustaša body politic. Pavelić trumpeted this fascist openness to limited religious plurality by converting Zagreb’s House of the Fine Arts into a mosque in 1944.

The neoclassical-modernist pavilion-cum-mosque had only risen several years earlier, but it was already a weathervane for the region’s rapidly shifting political winds. Initially conceived as a monument to Yugoslav King Petar I, its design was an expression of Ivan Meštrović’s genius. Meštrović was Yugoslavia’s premiere sculptor, a proponent of the Vienna Secession, a disciple of Rodin, and a firm believer in the unity of the South Slavs, the ideological adhesive that bonded Yugoslavia between the wars. His new art pavilion honoured Petar I, a scion of the Serbian Karađorđević dynasty who, from 1918 to 1921, was the first sovereign of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – the predecessor to Yugoslavia. Yet when the pavilion opened in 1938, the rabidly anti-Serbian Ustaše were already consolidating power in Italy under the patronage of Mussolini, who hosted Pavelić in exile for over a decade. Less than six years later, the building was re-dedicated to a dramatically different cause: Muslim-Catholic unity in the new ethnic polity, the Independent State of Croatia. Changes to the building were swift, and mostly cosmetic: the three minarets and interior ornamental motifs befitting a mosque.

These additions proved ephemeral. After the war, Tito’s partisans quickly transformed the building’s function and name again – by 1949, it had become the Museum of the Revolution. This proved to be the site’s lengthiest incarnation, at least thus far. The Museum of the Revolution persisted until 1993, when, in the wake of Croatia’s withdrawal from Yugoslavia and the subsequent war, the building reverted to its original function as an art pavilion and headquarters for the Croatian Association of Artists. Although it remains an exhibition space today, residents of Zagreb still colloquially refer to the building and its surrounding neighbourhood as Džamija, ‘the mosque’, without reflecting on the fascist genealogy of the title. Paradoxically, a trip to Zagreb’s ‘mosque’ does not usually end at the city’s actual Muslim house of worship, a Yugoslav-era campus in a relatively poor, peripheral neighbourhood. Stranger still, ‘the mosque’, a linguistic relic of the Ustaše, resides at the centre of the Square in Honour of the Victims of Fascism, a public space that explicitly condemns Ustaša depredations.

Whether or not Nurkić considered this dense history when he posted his Ramadan tweet featuring the fascist-era image of the mosque, his provocation was clear – the shot scored. One reply to the tweet denounced him as an Ustaša, while another leaned on a common racial-religious slur, branding him a ‘Turk who sold his faith for taxes’. A wag suggested that he had failed to understand the difference between the NBA and the NDH, the Croatian acronym for the Ustaša state. Supportive replies were less common, though a few neo-fascists reared their heads to salute the Portland player. Nurkić’s tweet also inadvertently called attention to an anniversary that passed largely unnoticed in Croatia and the region: the eightieth anniversary of the foundation of the Ustaša state only a few days earlier, on 10 April. In Jutarnji List, Zagreb’s daily paper of record, the journalist Robert Bajruši pointedly lamented that ‘the institutions of the Republic of Croatia have absolutely silenced this terribly important event – terrible in the literal sense of the word’. Nurkić’s Ramadan greeting did Croatian institutions one better, though not in the manner Bajruši might have hoped.

Many in the region reasonably claim that official silence is preferable to stoking the smouldering flames of communal antagonisms. Pavelić continues to haunt Croatia in many spheres beyond the circles of the far right that openly laud his legacy. Postcards and memorabilia from the Independent State of Croatia, including the very photograph of the mosque that Nurkić repurposed for Ramadan, sell for exorbitant prices in Zagreb’s flea markets, sandwiched between Iron Crosses and busts of Tito. Yet Pavelić and the Ustaše have no place in official memory today – a muteness that contrasts starkly with the socialist era when they were bugbears and collective enemies par excellence.

This official muting of the Ustaša past is a condition of possibility for the political successes of Croatia’s contemporary centre-right party, the Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica, HDZ). Nostalgic praise for the Ustaše circulates openly in the right-wing circles from which the HDZ draws some of its support, applauded by figures such as the ethno-folk balladeer Marko Perković, known popularly as Thompson. The party itself, however, aspires to the respectability of its Christian Democratic brethren elsewhere in Europe, and officially abjures the Ustaša legacy. Rather than Pavelić, it is Franjo Tuđman, the first president of independent Croatia who died in 1999, who personifies the nation-state today. Tuđman epitomizes a polite Croatian nationalism, as opposed to the barbaric nationalism of Pavelić and the Ustaše. Yet the two are not so easily quarantined. In the context of the warfare of the 1990s, Tuđman and the HDZ partially rehabilitated Pavelić and the Ustaše as earlier architects of Croatian sovereignty. This political resurrection was entwined with the parallel rehabilitation of another World War II-era fascist movement, the Četniks, on the part of Slobodan Milošević and like-minded Serbian nationalists. The violence of the 1990s was the crucible for a politics of memory in both Croatia and Serbia that found new uses for the Ustaše and Četnici, respectively.

Zagreb recently erected a monument to Tuđman, cementing his status as an embodiment of the nation. Pavelić’s legacy in the city is far less evident. Several weeks ago, I visited the ruins of his official residence, Villa Rebar, on the slopes of the Medvednica mountain north of Zagreb. It rots anonymously at the end of an unmarked dirt road, inhabited only by racist graffiti and a hodgepodge of litter: broken DVDs, condom wrappers, beer bottles. In a room that was once a cocktail lounge, I discovered a pile of discarded primary school textbooks, including a history primer that no doubt fails to mention his name.

Elsewhere, however, Pavelić’s memory resists ruination, and stirs with troubling new vitality. I witnessed stirrings of this resurgent potential several years ago on a summer morning in Madrid’s San Isidro Cemetery. Just as Mussolini sheltered Pavelić in the 1930s, Franco provided safe haven for him near the end of his life; though he initially fled to Italy and then Argentina and Chile after the war, he died in Spain in 1959 as the result of an assassination attempt in Buenos Aires several years earlier. Pavelić’s grave in San Isidro is a potent site of Ustaša memory. When I arrived, I found two strapping young men taking selfies in front of it. Several bouquets had already been deposited that day, and I heard more Croatian than Spanish spoken during my sojourn in the graveyard. Upon departure, I asked the cemetery gate attendant whether Croatian visitors were frequent – ‘Yes, of course’, he replied, ‘they come to see their leader.’

For Muslims, Ramadan is a time of abstention and spiritual reflection. As the month in which the Qur’an was first revealed to Muhammad, it is a period of heightened awareness to the entailments of Islam. It is also a season of peace, when even the most entrenched conflicts frequently abate, if only for a time. Regrettably, Nurkić failed to consider these entailments of Ramadan before tweeting the image of Zagreb’s erstwhile fascist mosque. Had he done so, he might have refrained from such a belligerent incitement in a context in which peace is still a recent achievement. Still, he was evidently unfazed by the conflagration he ignited on Twitter. He went on to score eight points the following day in a close loss to the Boston Celtics.

Read on: Catherine Samary, ‘A Utopia in the Balkans’, NLR 114.