A Pedagogy for Anti-Racism. Reflections from a Classroom and Beyond

by Sahana Udupa

This blog was originally published on February 21, 2023 in boasblog.

In this blog piece, I build on classroom discussions triggered by an ‘image exercise’—when I invited students to choose an ideal image for the home page of any anthropology department—as a gateway to think through some pertinent issues that have emerged while teaching topics such as extreme speech, nationalism, racism and decoloniality at different institutional spaces in Germany. I ask what this reflexive journey in and beyond the classroom as an immigrant scholar might tell us about envisioning ways to teach politically and emotionally charged topics within the disciplinary scope of anthropology and the crafting of a critical classroom more broadly. As I navigate the two registers of the pedagogical and the personal, I am attentive to unfolding transformations in Germany and elsewhere that have paved the way for greater anthropological engagements around issues of racism and xenophobic right-wing movements.

“I feel uneasy to be associated with a discipline that welcomes people with an image showing a white researcher surrounded by a bunch of black people”, remarked a student of anthropology, mildly nodding her head in disapproval, during a discussion at the decoloniality/postcoloniality seminar I taught in 2020. Her immediate reference was the classic image of Bronislaw Malinowski sitting alongside his research subjects on the Trobriand islands, with legs dangling down, and his long boots and a full white suit standing in contrast to the bare feet and bare chests of the Islanders. I could notice there were other subtle contrasts that made the student feel uneasy about using this image as the showcase piece of anthropology. Still gathering the thoughts on what might have caused her to distance herself from the image, she could however quite easily and instantly point out an obvious point of her discomfort—the stark color line that demarcated the boundaries of the researcher from the research ‘subjects’. She was clear that this is an antiquated mode of anthropology that she does not relate to. Indeed, it makes her cringe with embarrassment.

Our student expressed her unease about the classic snapshot of (colonial) anthropology while responding to my invitation to the course participants to select an image that they thought should appear on the home page of the official website of any anthropology department and discuss whether their choice aims to continue or dismantle existing representational politics of anthropology institutes. This “image exercise”, as we called it, was launched on the very first day of the course and it continued until the end. Moving stepwise, it started with students searching an appropriate image online and verifying the source and credibility of the image. Next, students gleaned the context of where they found the image, wrote a caption for the image, discussed their choice of images in the classroom, and finally submitted a mid-term assignment comprising the image, the source, the caption, and a brief explanation for why they thought this image should be on the home page of an anthropology department. An exercise that I started almost intuitively ended up triggering a wave of discussions inside the classroom—heated, engaged and reflexive. It stirred up, in unexpected ways, inchoate political positions that waited for clear articulation before others—in the immediate context of the classroom—but also more importantly, to oneself. With the images and captions tied to them, students and I were together navigating different discoveries about our discomforts and certainties, trying to discern the political meaning of how we felt and why.

Many students, partly echoing the theme of the course, observed that the images of the removal of statues or demands to decolonize the universities, especially on the South African and UK university campuses, should be seen as a signature event in the history of anthropology (Figure 1). As Isa Bojaj, one of the students in the class saw it, the felling of statues of slave owners “symbolizes the generational movement that is focused on eradicating socio-economic and racial biases that have so far been accommodated by elite universities”. Yoni Kron, another student, was convinced that the images of the “decolonizing appeals” with anti-racist comments that demonstrators wrote on the contentious statues should be “seen as an essential aspect of modern anthropology to reprocess its past in taking part in establishing global hierarchical structures, while actively trying to ease and change them for more global equality.”

Typifying the repertoire of a digital native, Sophie Lösch, another participating student, selected an Instagram post to convey a similar urge for change in the image politics of the discipline. As she elaborated, the post she selected about the British museum objects used the style of a sarcastic reply common in online interactional frameworks to drive home a political point about colonialism (See Figure 2). She wrote, “In my opinion the message in this image draws attention to the very relevant issue that a lot of objects of European museums are actually stolen from colonized countries. That these objects are still exhibited in European Museums showcases that colonialism and neocolonialism are still present nowadays.” For this reason, she thought, the image could clearly relay the kind of political message that contemporary anthropology should ideally convey.

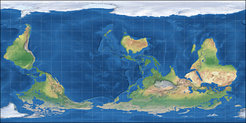

Carolin Dürr, another student in the course, recommended a picture of a “South Up” world map with Asia and Australia at its center, without the nation state borders and shipping routes. She annotated this image selection with a clear explanation. “This would be my choice for an anthropology department website picture”, she wrote, “because it literally turns common (internalized) Eurocentric and colonialist assumptions upside down. What’s ‘supposed to be’ on top is now at the bottom, neither the U.S. nor Europe are at the center. Combined with the lack of border indications, shipping routes or similar markers of human subordination and categorization of the world, such a visual can prompt a questioning of taken-for-granted notions…about inhabiting and researching (in) the world.”

Across these image selections and articulations of their relevance, the desire for representing the discipline as a shifting, ‘modern’ discipline becomes vivid. Some students explicitly characterized their image choice as the new generation’s eagerness to see the discipline declare its responsibility and responsiveness towards its past, and more importantly, towards the futures it promised. As Yoni Kron articulated, “…ideally, anthropology could bring [this] awareness and acceptance to the public”. In their view, as I interpreted them, such images helped to highlight that the normative center-periphery logics of anthropological inquiries and the associated ideas of discovering ‘difference’ in a hierarchical world system were constitutive of racialization. By inverting these logics, the images could signal the collective will to change the discipline’s outlook towards the world.

Such image choices resonated with anti-racist movements and broader contestations surrounding academic knowledge making that are mobilized especially on global social media channels, but the scene inside the classroom was far from a unison chorus. Many students selected the images of groups of people portrayed in computer animations or oil paintings to signal the discipline’s unique vantage point of exploring people as social groups rather than as individuals. Often such images were set against the background of a globe or an expansive panorama to indicate the discipline’s interest in exploring the world distinct from one’s own. Interestingly, in direct contrast to the unease expressed by a student about the use of the Malinowskian ‘field’ image, at least two other students felt that this classic picture from the Trobriand islands expedition adequately symbolizes the spirit of the discipline because it highlights the paradigmatic shift towards long term fieldwork and immersive forays into a ‘foreign’ land, and thus fully merits to be displayed as a pivotal image for an anthropology institute. Others limited the scope of its significance to how it portrayed the history of the discipline. Some felt that by exposing the researcher in the field, the image could unravel the conditions and power relations of doing research, but the image in any case, according to them, profoundly conveyed the distinctness of anthropological inquiry.

In this blog piece, I hold on to the “image exercise” as a gateway to reflect on some pertinent issues that have emerged while teaching topics such as extreme speech, nationalism, racism and decoloniality with German speaking students, international exchange students and EU Erasmus students across at least three different institutional spaces in Germany, and what might this reflexive journey tell us about envisioning ways to teach emotionally and politically vexing topics within the disciplinary scope of anthropology and the crafting of a critical classroom more broadly. Making use of the free-flowing format of a blog piece, I switch between the registers of the pedagogical and the personal, weaving in moments of immigrant encounters and navigations in the university space-time alongside my situated and partial knowledge of higher education as I have personally experienced it in the context of German “ethnology” over the last decade. In these years, I have moved between different cities and towns in Germany, with years of growing up in India and shorter stints in the US and Hungary profoundly shaping my immigrant experiences. As I navigate the two registers of the pedagogical and the personal along this journey, I am attentive to the transformations unfolding within and outside the university spaces, which are paving the way for greater anthropological engagements to address issues of racism and xenophobic right-wing movements.

Image politics and immigrant encounters

Much like any other institutional spaces, images hung on the walls of anthropology institutes bear evidence to the discipline’s practices and histories, represent its scholarly ambit and intellectual intentions, as well as signal its ambitions around how it wants the world to perceive it. Importantly, as semiotic formations and affective registers, images are particularly significant for the ways in which students come to embrace and evaluate the discipline, and how the faculty—old and new— grasp the subtleties of institutional traditions around the discipline.

A personal experience that triggered my attention to the pedagogical potentiality of the “image exercise” occurred on the very first day of my visit to an ethnology institute in Germany. As I was strolling the corridors, I came across an image of an Indian woman clad in a saree. Her hands were folded before a deity, with eyes closed and the neck stretched slightly upwards, towards where she perhaps saw the divine power. Looking at the picture, I thought, well, it could have been my aunt, sister, or cousin in her solemn moment with the deity or, it could have been myself. What was the picture doing there? Why was it in a corner where people would generally gather to have a cup of coffee and chit chat? I am still not able to articulate the unease of witnessing this picture, but what intrigues me is the striking similarity of this visual framing across several images hung up on the walls of anthropology institutes or their websites—a framing that holds the characters in a space of immutable difference. The vivid colors, things ‘out of place’ in the background or the sheer ruggedness of everyday living portrayed in these images frame the represented space as distinct from one’s ‘home’ and a ‘world out there’, marking also, in this case, a difference from the (sub)discipline of European ethnology and other social sciences and humanities disciplines.

There is perhaps nothing wrong in visually documenting ‘different’ cultures, and the intention of the image exercise in the classroom was not to place a cordon sanitaire around certain images but rather to drive the discussion beyond blind approval and denigration. As we debated this, I could pin down my discomfort to the demarcation of boundaries between home and field evoked in these visual cultures. Can such an intellectual culture of ‘difference mapping’ bode well for an anthropology of the world that is rapidly globalizing? The kind of globalization I am referencing here is not the assumption that national boundaries are dissolving (the contrary is true), but the mediated flows of images, people, discourses and theories as starkly exemplified by social media networks—the latest manifestation of globalizing media—which, among other forces, push us to reassess the epistemological grounds of difference mapping for the discipline.

To be sure, such connections are not always benign, inclusive, or forward looking. One does not have to look hard to realize how xenophobic right-wing groups have ramped up anti-immigrant, misogynistic, and racist discourses by sharing the content, formats, and styles of exclusionary extreme speech across the globe. It is precisely for this reason that anthropology might benefit more by seeing the connections rather than inscribing spaces within the frames of difference and alterity. It is for this reason that the image sitting at the corner has troubled me as something that could not only have infringed upon the solemn moment of a person offering prayers to her deity but its (dis)location conveyed a sort of cultural alterity that seemed antiquated as a frame for a connected world. This does not mean that people pray the same way or that people pray everywhere (and so why this image). The point is not about empirical comparison. It is about the abstract framing of difference-on-display dotting the institutional spaces of anthropology, in ways that difference speaks not to pluralism but sits as elements captured for documentation and detail, awaiting analytical clarity. These epistemological moves already constrain the potential of the images to say anything more than signaling a distance—as instantiations of a rupture between this and that, here and there, and more insidiously, us and them.

The image exercise in the decoloniality/postcoloniality course was in some ways a precipitation of different kinds of unease that some students and I have experienced around images that have come to represent the discipline in this part of the world. A reckoning with the images, I would believe, urges us to rethink ways of engaging with issues such as racism, extreme speech and xenophobia in pedagogy and scholarly exploration. If racialization is the enactment of degrees of domination/subordination (Wynter 2003), it would be important to recognize that locating difference in terms of hardboiled cultural boundaries might not be the best way forward even though it might befit the liberal pieties of ‘understanding’ and ‘accommodating’ difference.

Pedagogy around proximate exclusions

Even more, the discipline’s problem of (and with) representational politics provokes a host of pressing questions. The question around how we might raise issues of power and exclusion inside and beyond the classroom looms large. These challenges are particularly hard for immigrant scholars bearing the marks of racialized categories and even harder with minoritized subject positions based on gender and/or ethnicity. Scholars bearing these ‘traces’ might often feel that they embody the very difference that students at the ethnology institutes are primed to recognize and embrace. We are, in some sense, ‘authentic’ and ‘ethnic’ at the same time. The pedagogical and scholarly task of engaging such experiential realities—including keen reflexive attention to the privileges of education, caste and cultural capital we carry—towards anti-racist critical thinking should also deal with the nagging sense that immigrant scholars might be tolerable to the heirarchical organizational spaces so long as they don’t press any point too hard. The morality of benign accommodation in these spaces echoes the notions of “German liberal tolerance for unthreatening foreign identities” (Amrute 2020, 194) and notions of the ‘good migrant’ as docile and rule bound. A ‘good migrant’ blends well with the desire to safeguard the normal, the familiar, the routine, the regular. Such framings afford ways to be accustomed to, if not willfully reproduce, “race avoidant” tendencies of cultural anthropology documented elsewhere (Brodkin 1999, 68), adding to the hesitation to engage with racist and exclusionary practices that are proximate and those that could baffle one’s own existential worlds (and the privileges that come bundled with them).

The challenge before critical scholarship is therefore to build pedagogies to interrogate the here and now of racism—its globality as well as its troubling proximity to our own homes; its spectacular aberrations as well as its enfolding into the infraordinary and the banal. In the course I taught on nationalism and populism, for instance, I invited the students to locate expressions of mediated nationalism in their midst and think through this ethnographic case in relation to different scenarios we had examined in the class. In so doing, I encouraged them to draw on several impressive anti-racist projects underway in Germany across civil society, state supported actions and academic initiatives, including student led projects and those evincing a different relationship with images.

Engaged ways of teaching and researching racism, xenophobia and extreme speech come with several risks. Especially in a networked world, critical research and teaching face the risk of being derailed, disrupted or threatened by diffused and powerful groups of xenophobic actors who indulge in academic trolling—a digitally enabled practice in which right-wing vigilantes or folks who are just ‘irritated’ by ‘politically correct’ positions begin to follow, heckle and shame academic researchers and progressive voices online. For this reason, it is perhaps even more important to craft classrooms where students are able to recognize racism as it comes clothed in a variety of styles and forms—as memes, ‘facts’, counters, fakes, trolling and so on.

Commitments for a critical anti-racist pedagogy in a networked age require the strength to confront regressive tropes on different scales—from translocal social media to the very local institutional spaces (Udupa and Dattatreyan 2023). The emotional and intellectual stamina to imagine different futures including critical reflexivity about one’s own complicities is vital to inspire systemic changes—and not merely transient tactics—for justice and equity across multiple national, local, and transnational spaces that shape racism as an entrenched structure of exclusion and subordination. Towards this, we need a pedagogy that does not acquiesce to oppressive politics or reprise the familiar circumstances of liberal accommodation but causes a meaningful and dignified disruption—a consternation that could get us to think within. Perhaps we can begin with the images hung on the anthro walls.

References

Amrute, Sareeta. 2020. “Bored Techies Being Casually Racist: Race as Algorithm.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 45 (5): 903–33.

Brodkin, K. 1999. Race, class, and the limits of democratization in the academy. In Transforming Academia: Challenges and Opportunities for an Engagaed Anthropology (edited by Linda Green Basch, Jagna Wojcicka Sharff and James Peacock), pp 63–71. Arlinton, VA: American Anthropological Association.

Udupa, Sahana and Dattatreyan, Ethiraj Gabriel. 2023. Digital Unsettling: Decoloniality and Disposession in the Age of Social Media. New York: New York University Press.

Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3 (3): 257-337.

Sahana Udupa is Professor of Media Anthropology at the University of Munich (LMU München) and principal investigator of the For Digital Dignity research program. Her publications include Digital Technology and Extreme Speech: Approaches to Counter Online Hate (United Nations, 2021); Digital Unsettling: Decoloniality and Dispossession in the Age of Social Media (New York University Press, 2023, with E.G. Dattatreyan) and Digital Hate: The Global Conjuncture of Extreme Speech (Indiana University Press, 2021, with I. Gagliardone & P. Hervik). She is the recipient of Joan Shorenstein Fellowship at Harvard University, European Research Council Grant awards and Francqui Chair (Belgium).