China’s stained glass windows

by Naomi Hellmann

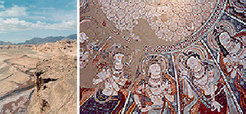

Right: A traffic stall for road construction facilitated this shot of slanted layers of rock and sand from the window of our car.

I came back from two amazing weeks in China's most northwestern province of Xinjiang. I actually went with UNESCO to see first hand our work on the restoration of the 5th to 9th century Buddhist mural paintings. I ended up worlds away after leaving the town of Kuche (Kuqa) and the center of Qiuci Grotto art for the border region of Tashkurghan, past Kashgar, the vibrant city fact and fiction once central to the dynamic Silk Road, and amongst the towering mountains that beckon towards Pakistan.

From Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, we drove in 110 degree weather (40+ C) over sparsely populated desert terrain and endless highway. Paved road is actually a welcome commodity though when you're not assured of it. Barren, mountainous landscape in hues of pale green, yellow and brown, blended into shades of gray in the sweltering heat before we finally arrived in Kuche, where even the grimiest of showers felt like an oasis.

Like most cities in China, Kuche's nondescript features belie the spectacular attractions that surround it and since most are relatively inaccessible, it is not inconceivable to be alone in a country of over a billion without a single person or building as far as the eye can see. The highlight of the Kumtura grottoes are two caves discovered in the late 70's with some of the most well-preserved Qiuci art in existence as far as I know. The interior of the caves are pitch black until a flashlight reveals two elaborately decorated domes carved into the ceiling with panel drawings in vivid color, each with a different detailed portraiture related to Buddhism.

It is a miracle in itself that they have not been utterly destroyed by an earthquake or the centuries of other destruction that mar most of the several hundred other caves that dot the surrounding region, including the spread of Islam beginning in the 9th century and other negligence through even today.

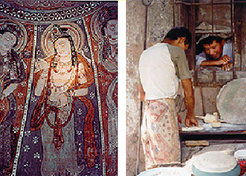

Right: Making bread “nang” in Kashgar.

Kizil Grottoes is another more famous site in the region that is rapidly developing with hideous architecture that is nothing but disrespectful of the surrounding environment and has no perspective on the future. But I spent a relaxing evening there to pick my way through a field of sweet grapes for breakfast before walking along a stream through sandy mountains and overgrown grass to happen upon my first spring. I went alone with the stubborn mindset that I could keep going despite a warning from the person from the Qiuci Grottoes Research Institute that I was with, who mentioned that I would know I was at the appropriate destination once I could go no further. As it happens, you walk until you are all of a sudden engulfed by rock face that appears to be weeping and forth is certainly not an option. It is a mystery as far as I was told as to the how the water is pushed from under the earth to seep through the crevices of the rock to appear like a myriad of trickling waterfalls from nowhere.

The region is in fact so dry that the rock crumbles quite easily into sand.. another woe of preserving the mural paintings that decorate the interior of the caves en masse. I was particularly pleased with my creative intuition when it dawned on me that the Buddhist cave art is somewhat similar in essence, I felt, to the stained glass windows that decorate many cathedrals in the West... but I digress. Perhaps you'll be more receptive of my romantic interlude though than the few Chinese people with whom I tried to sincerely share what I was convinced was my sheer brilliance, the first problem being how to describe stained glass windows in a foreign language to people who have never left the country, if even the county. .. i reiterate, sheer brilliance.

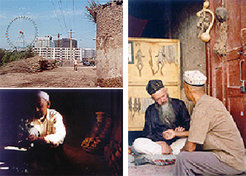

Right: Traditional Uyghur medicine in Kashgar.

In a twist of fate, I was joined by three people at Lei Quan (the name of the spring) to whom I owe much of the joy of my travels in Xinjiang and certainly, the rest of my trip. They are Chinese artists who had spent time at Kizil drawing bits and pieces of the remaining art and we ended up in long conversation before some one came looking for me convinced I was completely lost. After two more days in the Kuche region surrounded by towering gorges, other remote caves and outstanding scenery, the four of us took a five am train to Kashgar.. from which point on I severed my few UNESCO ties unwilling to give up my independence for the convenience of "official".

Kashgar offers an interesting perspective on the development of society in China and the unharmonious rapid transition of time. A large Ferris wheel and snow white and the seven dwarfs sit on the banks of a polluted lake with tacky Han Chinese pavilions in front of crumbling Uyghur brick housing hundreds of years old and the remaining part of traditional Kashgar. As in Lhasa, it is starkly divided between new and old, Han and Uyghur (ethnicities), relative wealth and poverty, government and commoner, etc. and I would highly question the notion of "progress" in the development that is boasted of and China's unusually phenomenal "growth" statistics.

Our own group grew to seven in Kashgar, and I can truly say that I could not have been luckier in meeting some of the nicest, most down-to-earth and caring people. After two days, we took the bus together to Tashkurghan, the Tajik autonomous region just before the Pakistan border, and I was again thankful to travel over with at least a familiar face in such a foreign region. Nonetheless, I actually resemble many of the people there, who look far more Central European than Asian despite their national Chinese ID... a pleasant change in perspective from the homogeneity of Beijing.

Right: Karakul Lake on the Kharakorum Highway through the mountains that lead to Pakistan.

Tashkurghan was memorable for the warmth of the people who accept you as family, including the five adult children and their parents in whose house I stayed. Life is languid at best, dependent on the sun and stars, and needs of the cattle rather than economics or globalization. Though unlit lamp posts and accurate traffic lamps on streets without cars currently still under construction allude of things to come, I’m still not convinced of what many people seem to do, or not do, for an existence, in particular the younger, able generation. As for traffic, it’s mostly pedestrian or creaky “taxis” from which I was amused to observe a sheep hop off first followed by a man with his leg in a cast, not to mention the remaining crowd that was still sunken in the crevices of the sloping interior. Army vehicles also pass, not that their occupants seem to pay any heed towards respecting the surrounding environment, natural or cultural.

Right: Fresh figs, a seasonal delicacy and hot commodity in Kashgar.

I left Tashkurghan to return to Kashgar with some of my best memories from China. The group I was with left for the mountains to paint in regions that appear to have escaped all encroaching modernity. Without electricity or much to describe materially, the region has remained impermeable to the WTO and non-Chinese citizens as of yet. It is also almost 5,000 meters above sea level and not without danger.

Right: Two Muslim women remove the traditional head veil that covers their face. Dress varies widely in Kashgar.

Once, I wrote from Gansu and Qinghai provinces that perhaps our sweetest rewards are in the farthest reaches and if so, my travels to Xinjiang were a dream. Returning to the stark faceless, reality of Beijing where all that glitters is certainly not gold, I jostled with a mob of people in the mad rush for a seat on the bus at 1 am in the morning at Capitol Airport.. a far cry from the slogans advocating a civilized society that Beijing and much of eastern China take such pride in. Thankfully, I will leave again in two weeks, this time seemingly much for good.. Months ago, I had a vague idea that time-wise I would probably be in China for a few years and so it seems appropriate for me to leave now, even without the most concrete of plans and even if I’m not necessarily leaving the country per se. Besides, if I’ve learned nothing else from being here it’s to forget trying to plan anything around here anyway or you miss out on everything.