Director: Dan Smyer Yu

Pre-production fieldwork: Dan Smyer Yu

Film type: documentary

Length: 55 min.

Viewing status: rough cut

Technical exclamation: shot on RED proudly!

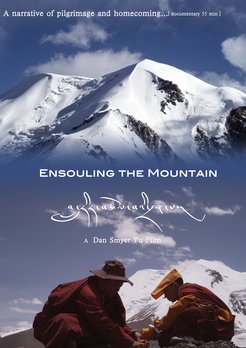

Ensouling the Mountain

Dan Smyer Yu on Film Making

by Dan Smyer Yu

Synopsis

This ethnographic film documents a pilgrimage of lamas, scholars, writers, filmmakers, and students to Mt. Amne Machen (Amne Machin), one of the nine Tibetan sacred mountains, located in Golok, Amdo, currently in Qinghai Province of China. Most pilgrims, as an integral part of the film crew, are both behind and forefront of different scenes. The film crew pulls its focus on how Amne Machen symbolizes home, belonging, and humanization of one’s native landscape. As Amne Machen is known as lha-ri or “soul-mountain” to which local communities and prominent historical figures entrust their collective memories, the sense of home and place-making are the primary topics of the pilgrims’ reflections. Through the narratives of the pilgrims and cinematic capturing of the awe-inspiring landscape of the mountain, this film relives powerfully gripping moments when place becomes a placeless, flowing cultural consciousness in the minds of the pilgrims.

Ensouling the Mountain is actually my third film. The second one entitled “Sentience of the Earth” has a rough cut version, but because I treated it as my “eco-cinematic” experiment and got carried away with minimizing human presence and no voiceover or narratives of human subjects in the film, my donor is reluctant to pump additional $$ into it; so it is on hold. Ensouling the Mountain project is going well but has taken many turns, too. Its preproduction was shot with eclectic supports – Max Planck Institute funded my ethnographic work but not the filming part; members of my former film co-op in Beijing returned their felt indebtedness to my support to their past projects; two film scholars and makers at Beijing Film Academy insisted my shooting the documentary after reading its outline; one VP at a RED gear rental company in Beijing helped me re-house a wide-angle still zoom lens into a cine lens for landscape filming; my Tibetan writing friends and former graduate students reunited with me volunteering as crew members; and finally the company, which bought my film co-op gear when I was moving to Germany, happily loaned me a brand new RED Scarlet camera commissioning me to test it out in a high altitude environment (5,600 meters) but hoping someday I’ll be able to pay them back. Although it has taken many turns, I nevertheless see how great it is to be an anthropologist locking myself in a “gift economy” with numerous different individuals and institutions – truly experiencing everything is relational. What goes around comes around; what is not circulated will never be in the circuit. This is a wonder of doing fieldwork.

I am very fortunate that this film came out of my fieldwork this past summer, which was initially intended to yield ethnographic contents only for two chapters in my new book. The moving images in the film are already making my writing more telling and convincing about my development of a theoretical perspective that a place’s subjectivity is not always only the result of human affective, social, and cultural investment in it. It also comes from the uniqueness of its own geology and topography, which speaks to human dwellers and visitors. Another theoretical development that I am working on is what I call the “placeless place” in human consciousness. It can be an imprint of a physical place on the human mind. In other words, let’s say, a place is physically situated and immobile, and yet becomes mobile when it is turned into a placeless place in human memory or cultural consciousness. Sometimes people are physically displaced but are reunited elsewhere based on the identical placeless place remembered in their individual minds. Different diaspora communities are examples. Edward Casey once said, “Place is memory…Memory is place.”

I have done fieldwork in Golok six times since 2002. I went to Mt. Amne Machen in 2007 but didn’t prepare well enough for a circumambulation. My last time in Golok was 2010 when I was visiting the young Siddhi Lama and his uncle Akha Shamba, a monk, who just returned from their trip to Nepal and India. Both are in this film. They are natives of Golok. Five other Tibetan crew members are all from Amdo (Qinghai part) but currently live in Beijing as writers and graduate students. None of them have been to Amne Machen. Most of them headed straight from their home village or town to Beijing venturing into a new life style. Akha Shambha and I planned the routes since the rest of the crew members had not been to Golok.

This is not my first visual ethnographic work. In my experience, the feasibility of an ethnographic film project is often determined by how well the filmmaker has done pre-ethnographic work in terms of the location spatial details, event calendars, and close rapport with the community. I reject the approach that one enters a field site (a community) with his camera and starts shooting right away. You see, I reflexively use “shooting” rather than “filming.” The act of filming is symbolically violent and personally intrusive when the documentary maker has no prior relationship with the community. A camera may be designed as a “point and shoot” type but when it actually points and shoots one’s intended ethnographic subjects without prior relationship, it would often disrupt routines of the community. Siddhi Lama, Akha Shambha’s nephew, is twelve this year. I started taking portraits of him when he was three, the time when he was recognized by his home monastery as a reincarnate lama. He and his family are used to seeing me with my cameras. I have more details about Siddhi Lama in my book .

Last December Akha Shampa told me he was planning a pilgrimage with Siddhi Lama to Amne Machen. With his permission I broadcast the news to my Tibetan friends and students in Beijing, hoping, with my selfish reason, they would join the pilgrimage as additional companies and interlocutors for my second book project about place and imagination. Of course, I told them my research intent when spreading the news. Last March while I was in Beijing for a conference sixteen of them responded positively to my invitation. But, toward the early May the schedules of only six of them would be able to fit the timeframe of my fieldwork. Four of them had prior filming experience with my former film co-op in Beijing.

After my rough cut was completed, three film directors and one script writer in Beijing viewed it. They unanimously proposed the documentary be cut into two different films – one only retains the young Siddha Lama and his uncle Akha Shampa while another focuses on my Tibetan friends in Beijing. They felt the narratives of Akha Shampa and the scenes of him with Siddhi Lama are too good to be cut short. When suggesting this idea, they appeared more like viewers than reviewers/critics. They told me they wanted to see and hear more of the native voice of Akha Shampa and more of his feeling and affection for his home environment as opposed to the sentiments of the urban Tibetans, which they are familiar with in terms of pollution and discontents to modern life style. So, they suggested I shoot a separate documentary exclusively about Tibetans living in Beijing…For now I plan on finishing my book manuscript before I get myself preoccupied with more ideas for ethnographic filmmaking.