Blog | February 2020

Chinese Black Humor in a Time of Crisis and Despair

by Zhen Ma

“But stay positive, okay! We finally get a chance to make our country proud by just lying around at home”.

My friend consoled me with this message on the 26th of January at the end of our conversation about the coronavirus illness, now officially named COVID-19, which has taken 1666 lives, infected 68,589 people worldwide, and literally affected everyone’s life tremendously in China.

I answered her with an emoji of dumbfoundedness, and laughed.

It was the first day of the Lunar New Year, the most important festival for Han Chinese in China and beyond. Normally, it is a day in which the family gathers, eating hearty food, going to temples to burn incense, hanging out with friends, playing Mahjong, or just lying around at home. But nobody would try to make the country proud on that day.

I didn’t think about how to make my country proud that day, either. An empty stomach doesn’t have ears, I thought. It was the fifth day of my quarantine and I had to manage to get some food. To avoid bringing the virus to the village where I was conducting fieldwork, I had chosen to quarantine myself in a room of a hotel in Jinghong, the capital city of Yunnan’s Southern Xishuangbanna (Sipsongpanna) Dai Autonomous Prefecture since I returned to the city on the 21st of January after a short fieldwork trip to Tachileik, a city in the Shan State of eastern Myanmar. Jinghong is one of the most popular tourist destinations in China. With its tropical climate, diverse ethnic cultures and various delectable foods, it is especially popular for people from Northern China who want to escape the cold weather and celebrate Spring Festival during the vacation. At this time of year, main streets as well as small lanes of Jinghong are overcrowded with tourists, usually with small groups of families. However, when I went out that day, the tens of thousands of tourists who had been strolling around the streets of Jinghong a few days ago when I arrived in the city had disappeared. The usually busy streets were almost empty with only a few cars and scooters passing by. The popular restaurants along the two sides of the street where I was staying were all closed, without the chink of glasses and plates, the odors of frying garlic, ginger and spring onions in hot oil.

I had to find an open grocery store at least, I thought. Not only for getting life supplies, but also to get face masks which were much more important than life supplies those days.

“Do you sell face caps”? I asked the shop assistant of a small store opening at the corner of a street 20 minutes away on foot.

The man shook his head impatiently.

“Why you don’t wear one? You are in contact with so many people every day.” I asked him.

“It doesn’t work. The face mask I have cannot prevent myself from the virus. It is cotton.”

“Do you sell cotton ones then”? I asked with hope.

“No, not now”. He answered quietly.

I went into his shop to pick some instant noodles, sausages, cookies and milk, which I had been eating for five days straight. The most common conversations I heard during my short stay in the shop were: a loud question “Do you sell face masks?” followed by a quiet answer “no, not any more”. And then silence.

After getting out of the store, I went to a big pharmacy I usually went to hoping to buy one or two face masks.

“Do you have face masks?” I asked.

“No, we haven’t sold face masks for three days”.

“Do you know when your store will get supplied?”

“No ideas. But we have herbal antivirals, do you want some”.

“Thank you. I don’t think I need them at this stage”.

A woman who heard our conversation at the threshold of the pharmacy left without entering. “Don’t tell me I really have to make one with my bra”. The woman talked to herself.

The nurse in the pharmacy smiled. Without getting the joke, I left the pharmacy.

Everybody’s life was affected by the outbreak. At that time, people in this part of Yunnan, the very southwestern frontier of China, still felt the virus was far away. However, the anxieties caused by the shortage of face masks were real and close. All the staff of my hotel used their local connections to buy face masks from all over Xishuangbanna. One of them received 20 from his friend who is working in a tea factory in the neighboring Menghai County. We felt such a relief when we heard that the hotel had 20 face masks! But when I opened the one they distributed to me, I realized the masks were made for preventing dust in tea processing. They look almost transparent. I told the staff of the hotel that these facemasks did not meet the standard to keep us safe from the virus.

“So what do we do? Let’s make face masks with bras then.” One of them said, laughing loudly.

“I heard this when I went to a pharmacy this morning. Why are people talking about making face masks with bras?” I asked with confusion.

“Because some people already did”, she grinned from ear to ear, “I am wondering what is the smell”.

Frustrated that I still didn’t have a mask. I left the lobby of the hotel and didn’t payed any attention to the issue of bras.

In the evening, one of my friend sent a photo of a facemask (see photo 1) in a chat group and said: “the genius Chinese pranksters show off their talent again!” I suddenly understood the bra-made facemask.

Photo 1: A widely circulated photo of a face mask made from half of a bra (originally from the Douyin account Ying Jiang Chuangzuo de Yuanshen). Text at the bottom of the photo is: Since I cannot buy a facemask, I make one myself!)

There is a lot information, rumors, blogs, and essays of the spread of the coronavirus. The number of confirmed cases grows steadily, as well as fear. It was a challenge for many people, like me, who stayed totally alone, to keep calm. Many of my friends told me that they compulsively checked social media and the news hoping to learn about the virus and what was really happening in Wuhan, the center of the epidemic, just as I was doing. Chinese social media, such as Weibo (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter), Wechat (the Chinese equivalent of WhatsApp), Douyin and Kuaishou (like Chinese Youtubes) were all full of overwhelming information about what was happening in Wuhan. People were experiencing something like in zombie movies: In many cases one person was asked to stay under quarantine at home, and then all his/her family members were infected but none of them could get treated in any hospitals. Lots of doctors and nurses were infected and their colleagues were still treating people while wearing substandard facemasks; there was a dearth of medical supplies in hospitals in Wuhan. Personal stories were shared, like one about the 12 hour devastating process to get a bed in one of the designated hospitals for a seriously sick father when her Mom and herself had symptoms as well; a video of a girl crying alone in front of a hospital calling Mama……and Mama was in a hearse driving away; a 17 years old boy with cerebral palsy died after his father and his little brother, the only family members he had, were quarantined for 6 days….

Several of my friends told me they can’t help but cry in frustration, depression and the strong feeling of guilt, knowing other people are suffering grievously but not being able to do anything about it. So did I. But there was always also something circulating on social media that would make you laugh, maybe through the tears.

“It is hilarious, but it made me cry”. One of my friends wrote this sentence above several photos (see photo 2-5) of handmade facemasks on her Wechat.

Photo 2: A man wears a facemask made of orange peel in a hospital (photo from Weibo account Hamei) • Photo 3: A man wears facemask made of Instant noodles. (Photo from Weibo account Nuli huozhe de Women) • Photo 4: A man wears a facemask which is a baby diaper. (Photo from Internet) • Photo 5: A man wears a facemask made of bottles (photo from Weibo account Chengdu Chitu Qingnian)

Another friend shared similar photos and wrote “I laughed, but after laughter comes anger”. There has been a dearth of face masks in China since the outbreak. People outside Wuhan try to cope with the situation using their creativity and black humor, while people in Wuhan, especially doctors and nurses pay a high price, even with their lives. With a shortage of medical supplies, nurses had to make facemasks themselves between shifts. Social media flooded with questions, critique and protest. News and Weibo articles and editorials were censored. Black humor and photos survived. But even so, humor became unbearable for many of us. One Weibo user wrote: “please stop circulating those ridiculous photos anymore. They are not funny at all. It breaks my heart when I see people living in such a harsh reality.” However, there were more and more photos circulated on various social media of people actually wearing those facemasks. Because deeply in our hearts, we know that it cannot be just laughed off. It satirizes the harsh reality we are experiencing and shows the bitterness we are tasting.

Having failed to buy a facemask, and not knowing how to make one with my bras, bottles or orange peels, I tried to reduce my contact with other people as much as possible. I asked the housekeeper not to clean my room. I locked myself in the room with only one way of connecting to the outside world: social media. Social media was a space in which many of us found companionship. From social media, I found out I was not the only one who fretted about my parents and their unawareness of the way the virus spreads. Back in my home, a small town in Gansu Province in Northwestern China, my parents were coming up against a longstanding tradition. We have a tradition called “zuozhi”, which means visiting the family of the deceased in the first three days of each year for three years after the death. Every year, my father would go to visit those families which had lost their loved ones and burn incense and “paper” in front of the memorial tablet to cherish the memory of the dead. He wanted to go, otherwise he would feel morally wrong. He knows, of course, that the virus could transmit by shaking hands, face-to-face contact, and eating with other people. He also knows, that almost half of the population in the town travelled back home in the two weeks after the outbreak, and meeting people from Wuhan is not impossible. But the tradition and the morality associated with it became a burden for him. Like my hometown, the majority of China shares a tradition of Bainian, which has lasted for thousands of years. People living with this tradition know just how strong it is, especially for older generations. It is almost impossible for the younger generation and the local government to keep elders at home at a time when they are supposed to go to visit relatives and friends during the fifteen days from Lunar New Year to the Spring Lantern Festival.

Black humor turned personal concerns into shared laughs. Series of photos of so called “hardcore slogans” (see photo 6-8) started to circulate on Wechat and Weibo too. One of my friend wrote on his Wechat “This is a time to let the government know why you should really trust the people, rely on the people and be inspired by the people.”

Photo 6: Visit one’s home this year, visit one’s grave next year.

Photo 7: How to be filial children? keep your parents from going out!

Photo 8: Staying at home to avoid the infection, kick out even your father-in-law if he comes to visit.

Black humor was used by people in a time of crisis as a way of coping. Others use it as a novel but powerful way of resisting and critiquing. In one academic Wechat group I subscribe to, scholars started to circulate a photo of words and numbers (see photo 9). It was one of many ways Chinese people use to avoid the heavy censorship. We write something down and create a photo of the words and then post the photo, which cannot be found through word search algorithms and censored by the so-called internet policemen. The photo is about the mortality rate of the illness reported by the government (see the translation of the photo on the right side):

Photo 9: The miraculous coronavirus, is also a master of mathematics.

By sharing this photo, people were protesting and called upon the authorities to report the actual number of deaths rather than just meeting the predicted mortality rate published by the WHO (World Health Organization). Lacking credibility, the government has lost public trust.

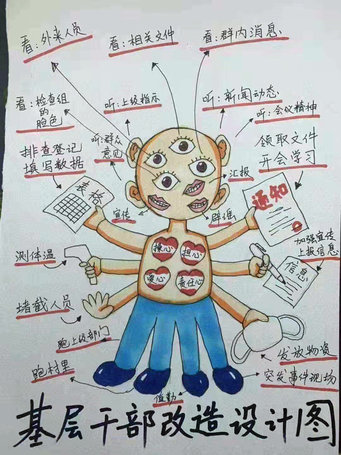

With the number of infected increasing, the central government decided to cancel the vacation of all the ganbu (cadres, the people who are working in local civil service) and ordered the whole country to enter into battle in defending against the spread of the virus. Both members of the committee of the village I was doing fieldwork in and my brother, who is working for a township government, expressed that they are overworked on many fronts that actually don’t help to prevent the spread of the virus, such as filling in lots of forms, accompanying local leaders’ visits and inspections and being on duty in various check points for testing passersby’s body temperature. I was worried about my brother too. It will be much safer for him to stay at home, rather than standing at a check points, interacting with his colleagues and lots of other people. I started to search online, how should he, as one cadre member working for the government, protect himself and question whether all the work he is doing necessary. The sympathy I had for my brother found resonance in social media. A drawing (see photo 10) revealed vividly and satirically the overloaded people who are working in local government agencies with four eyes, three mouths, six hands, four legs and four hearts.

Photo 10: A blueprint for reconstructing local cadres (Photo from internet. The origin of the drawing cannot be traced).

My brother sent the cartoon to me and said “the person who drew this must be a cadre him/herself. It is really a pity that we don’t have ‘three heads and six arms’ (santou liubi, a Chinese proverb to describe one has tremendous abilities in dealing with things)”. The cartoon demonstrates varies missions of local cadres: with four eyes, they inspect people from outside the region; read relevant official documents; read messages shared on chat groups; and read the mood of upper level inspection units; with four ears, they listen to orders from above; listen to news; listen to the people; listen to meetings; with three mouths, they give reports, disseminate information and refute rumors; with six hands, they fill in forms; test body temperatures; prevent people from travelling; distribute (medical) supplies; intensify propaganda and report local information; pick up official documents; participate and study in meetings; with four legs, they go to higher government agencies; go to villages; go on duty; go to deal with emergencies.

And they have four hearts, one heart for worrying; one heart for being concerned; one heart for caring; one heart for taking responsibility.

Unfortunately they are not mutant super humans, they are just ordinary people. My brother and his colleagues have to stand outside for 8 hours a day, sometimes during the cold nights of northwestern China’s winter in temperatures seldom above minus 10. For them, the cartoon, is a voice, a consolation.

Staying totally alone and surrounded by depressing stories and information, I tried to read jokes to fight the feelings of loneness, confusion, disappointment, anger and uncertainty. I started to realize: It was not news, information or truth I wanted to get from those hilarious photos, videos and essays, it was the laugh itself. At a time when we feel confused, threatened and surrounded by tragedy, laughing is a way of healing.

For days, it took no effort for me to make myself laugh because of numerous jokes, photos and essays circulated on social media. But on the night of 6 February, not even one single joke was circulated on any social media account because of the death of 34-year-old Dr. Li Wenliang. Dr. Li Wenliang was one of the eight whistle-blowers who warned of the spread of the virus in early December 2019 and was attacked as a rumormonger by the authorities. That night, Chinese social media was coved with howls of outrage and protest. People asked morbidly not only about his death, but also the long process of the death. His death was first reported by his friends and colleagues at 21:30. People started to mourn him but also to question the cause of the tragedy. With his courage and his inspiring interview, he had become a heroic symbol for many Chinese people. At 11:50, the WHO published memoriam for his death. Something ironic happened next, near 01:00, one Weibo user wrote Dr. Li Wenliang had been rescued by an ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation). Many people wrote “We kind of know it is an official rumor, but for the first time in my life I hope it is true.” Dr. Li was officially announced dead at 02:58 on 7 February. There was a public outcry over how the authorities tried to smooth over the public mood by fooling people. Lots of exposed chats among Dr. Li Wenliang’s colleagues show the hospital borrowed an ECMO three hours later when his heart stopped beating.

People were saddened by the death of Dr. Li Wenliang and became more and more disgusted with the government’s response. Then, on the third day of his death, people started to criticize the government with absurdity. An essay entitled “If you are not satisfied with your father, you yourself must become your grandfather” was circulated more than one million times. It was triggered by an old Weibo post of the editor in chief of the Global Time, Hu Xijin. He wrote: “If you think your country is not good, go to build it yourself. If you think the government is not good, do the civil servant examination and become a civil servant….”. The author of the responding essay wrote: “It appears like Mr. Hu has a perfectly logical idea. One should make the things he/she thinks flawed better. But we have had enough of this kind of logic. Do we really have to become something we are not satisfied with? Why should we pay a high price for mistakes made by others? Even giving up our own work!” Sure enough, the essay was censored. I did not create a photo of the essay. But I remember lot of sentences people made following the same grammar structure of “if you think … is not good, you go…”. One Weibo user wrote: “If you think the US is not good, you go to the US and become an American. If you think Japan is not good enough, you become Japanese.” Another one wrote: “If you think the security guard of your neighborhood is not good, you go to become a security guard”. More and more people commented in the end of the essay. One comment reads “What if I think the pig in the sty of my backyard is not good?” Another one reads “actually I think the toilet of my apartment is not good enough, too. Should I become….”

The crisis of the spreading of the coronavirus has bred a wealth of black humor. Sadly, our lives as they are lived through this crisis are examples of black humor themselves. When there are no spaces for people to live in real life, people live in virtual space, like Chinese people have been doing in the last 20 days. However, in a forcefully controlled society and heavily censored internet, even virtual space is dangerous. It is dark. However, through the black humor which people live through or have created, Chinese people share a reality and show a resilient attitude. If not, they at least make people laugh in a time of crisis and despair.