Trieste is Sissi with Piercings and Blue Hair

by Giulia Carabelli

‘Today my city is Sissi wearing a lycra body. It’s Sissi with piercings, blue hair and a salamander tattooed on her neck. Trieste still has the fingers of a princess, but also a nail-biting problem’. This is how Mauro Covacich, one of Trieste’s most renowned authors, captured, a decade ago, the complex interplay between Trieste’s imperial history, its nostalgic practices of preservation, and contemporary urban trends. If the past is vividly present in the grand cafés and their fin-de-siècle atmosphere, the refurbished Schönbrunn-yellow palaces reminiscent of Vienna, and a cultural programme that celebrates the memories of the Habsburgs, a few days in Trieste suffice to discover a myriad of trendy bars and cultural venues where appreciation of the city departs from the ubiquitous post-Imperial ambiance. For instance, Trieste’s local cuisine has been re-appropriated to become more environmentally-conscious, healthy, and hip, embracing the philosophy and practice of the slow food movement. In January 2017, the gallery DoubleRoom curated the exhibition ‘Sirene Queer’ (‘Queer Mermaids’) to discuss issues of borders, sexuality, and gender by approaching the myth of mermaids and tritons through the work of Fiore de Henriquez, the intersex sculptor who was born in Trieste, in 1921, to a noble family that was part of the Habsburg court in Vienna. Drinking coffees and spritz with new and old friends alike, I could not fail to notice the fascinating ways in which the past, the present and the future of the city collide and stride without necessarily seeking consistency and compatibility.

Sissi is the first to welcome me in Trieste

I encounter Sissi—the Empress Elisabeth, Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph’s charismatic, ill-fated spouse—shortly after arriving in Trieste, on the walk from the bus station across Piazza Libertà towards the city centre. She stands in a small green area, surrounded by benches where people sit, chat, and eat. Sissi never lived in Trieste, though her visits to her in-laws, Charlotte and Maximilian, are well-documented in a permanent exhibition located in their former residence, the iconic Miramare Castle. Standing with her back to the train station, Sissi was sculpted by Franz Seifert in 1912 thanks to funds collected spontaneously from among the local population. She stood in this spot for less than a decade before she was removed, to reside in storage until 1997 when the city’s administration included her in its urban regeneration plans for the area. Carla Fracci, the Italian ballerina, uncovered the repositioned statue – this ceremonial unveiling thus united two women who became, despite their many differences, globally-acclaimed and popular princesses. The move of the administration was not without contestations, especially on the part of those who condemned Sissi as anti-Italian. She was a mean woman who hated Italy. People are ignorant and they don’t know…thus the cult of Sissi. If only they knew the history… such was the disdainful explanation that a representative of a right-wing party gave to me later during my visit to Trieste. Sissi came to represent, in his words, a menace to those who struggle to declare Trieste italiana, rather than cosmopolitan. My developing appreciation of where Trieste belongs—geographically, politically, historically, and culturally—is a journey that I wish to share in this post. The changing fortunes of Sissi’s statue, and the ambivalences that they register, exemplify part of this journey.

Sissi and I, in Trieste

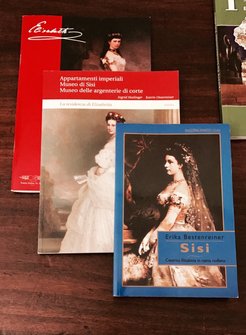

Searching for accommodation, I stumbled into ‘Il Rifugio di Sissi’ (Sissi's Shelter), a spacious apartment in the very heart of the city, a few steps from the Piazza Unità. Sissi’s Shelter promises to ‘offer a pleasant and very suggestive environment; a trip in the Trieste of the „Fin de Siècle"’. And here I am, touching the old furniture, admiring the owner’s curatorial skills; the old maps on the wall, the portraits of Sissi and Franz Ferdinand, and a thematic library for Sissi-lovers.

From my fourth-floor window, I can see Pietro Zandomeneghi’s sculpture, an allegory of the city as a maritime, trade and financial centre, on the top of Palazzo Tergesteo. The complex, whose name means ‘the Palace of Trieste’, was built in the 1840s and became an important financial headquarter and a meeting place thanks to its café. Although this café no longer exists, it was celebrated by the poet Umberto Saba as the place where Italians and Slavs met, late at night, alongside the billiards.

Soon, I encounter Sissi again, while reading about the traditional Triestine patisserie. Apparently, the famous Presnitz (a circular nut-filled pastry) may have its origins in a local competition to design a cake special enough to welcome Sissi to Miramare – the ‘Preis Prinzessin,’ or ‘Princess’s Prize’, eventually became Presnitz.

Sissi, Trieste, and the fantasy of what should be found

Sissi, the Empress plagued by eating disorders, familial problems, and an obsession with a healthy and active lifestyle becomes, in Covacich’s book, ‘Trieste Sottosopra’ (Trieste Upside-Down), the metaphor of Trieste. When we imagine Sissi, he suggests, we think of the film actress Romy Schneider or the many statues and paintings in which Sissi poses with her long hair, decked out in beautiful outfits. Yet Sissi was also a very unconventional woman who struggled to become what was expected of her, and what she expected of herself. This is equally true of Trieste. The city exerts powerful expectations: the desire to experience the splendour of the Empire, the hope to bump into one of the city’s many celebrated intellectuals, the opportunity to understand how the multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, and multi-religious identity of this city has inspired so many writers and poets. And there is Trieste as a lived environment where those expectations are constantly met and disappointed, revealing its very complexities. Surely, the city has capitalised on the idea of Trieste as a unique destination; tourism is a prosperous business here. Yet it seems that the majority of visitors are from Austria, attracted by the possibility of feeling at home away from home, with the view of the Adriatic helping to establish new connections between the former territories of the Empire.

I was curious to understand what it means to grow up in Trieste, a city where history is so ever-present: well… it’s that you feel it… if you are from here… you feel it… For many residents of Trieste, the legacy of the Empire is an intangible social force rather than a history lesson.

Trieste moves slowly – everyone with whom I speak repeats this to me. It’s comfortable and perhaps this is why people don’t want to change it, I am told. And yet, it moves. The sense of the grandiose past is everywhere but it fails to oppress, rather it becomes a reminder of the possibilities that the city holds. The young people I meet are aware of the limits set by living in a city that caters to the elderly more than to the youth, but I can hear in their words the feeling that something can and will change… there is a potential, have you been to Eataly? (A recently inaugurated, high-end indoor market where one can purchase gourmet food from Italy a walking distance from Piazza Unità, sulle rive, along the sea promenade). The façade facing the sea is a window … the entire thing! It’s stunning… you can have coffee there too, looking at the sea. And looking at this sea, towards the castle of Miramare from where Sissi departed on her many maritime adventures, I sat contemplating the beauty of a city where I got lost in time and found myself again in space, so many times, in just one week.