Fieldworking with Khenpo Sodargye – The Charismatic Mind of a Modern Buddhist Thinker

by Dan Smyer Yu

Buddhism becoming modern isn’t news anymore. Among scholars, Buddhist modernity or modern Buddhism is being extensively discussed. The geographic emphasis of this scholarly attention is often given to the Western Hemisphere as shown in the works of Charles Prebish (1971; 2011), David McMahan (2008; 2012), and Cristina Rocha (2011). I see this “Buddhist modernization” is also taking place in the homelands of different Buddhist traditions in Asia. The growing popularity of Tibetan Buddhism in contemporary Chinese society is a modern Buddhism at work. It is not because the canon of Buddhism is undergoing modern transformation but rather because Dharma teachers are becoming ever more mobile reaching out through new mediums of Buddhist conversion, public discourses, and personal practices. I’m not blogging about a theory within modern Buddhism but about a leading figure in modern Buddhism – Khenpo Sodargye – a Tibetan lama from Larung Gar Buddhist Academy in Sertar, Kham, currently western Sichuan Province of PRC.

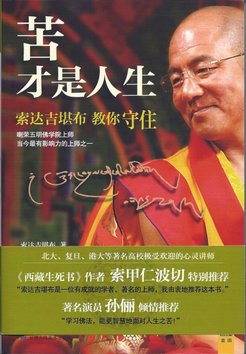

While Sogyal Rinpoche, Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, Neten Chokling Rinpoche, the late Chögyam Trungpa, and others are the icons of modern Tibetan Buddhism in the Western Hemisphere, Khenpo Sodargye is their counterpart in China, who is imparting what he calls “the Tibetan Code of Happiness” to the Chinese society in his latest bestseller Living through Suffering. According to him, the system of this “coded” message of happiness is nothing mysterious but “a science of spirituality” – a neologism he coined to represent the teachings of the Buddha with a contemporary flavor.

When I was finalizing my first book ![]() The Spread of Tibetan Buddhism in China in 2010, Khenpo Sodargye began his new round of engagements with Chinese mainstream society. This time, top universities, such as Peking University, Fudan University, and the University of Hong Kong, are his new field where he finds a special audience – the top students and faculty members of the most populous nation on earth. Not following tradition by giving his lineage-specific teachings, he is conversing with them on a series of ongoing hot topics of public discourses, such as religion-science dialogue, charity and the public good, and inner environmentalism and life ethics. Young university students affectionally regard him as “the Doctor of the Mind” and “the Scientist of Spirituality,” as he points out the pathology behind a whole range of the commonly felt states of the mind among modern Chinese , including depression, paranoia, anxiety disorder, alienation, affective disorder, to name a few. Coupling with his public lectures on university campuses, a series of his new books are entering the private collections of his young audience, e.g. Spiritual Remedies: the Only Cure for Mental Illness, Pure Land in the Human Realm, The Facts We Have to Face, and Receiving through Doing.

The Spread of Tibetan Buddhism in China in 2010, Khenpo Sodargye began his new round of engagements with Chinese mainstream society. This time, top universities, such as Peking University, Fudan University, and the University of Hong Kong, are his new field where he finds a special audience – the top students and faculty members of the most populous nation on earth. Not following tradition by giving his lineage-specific teachings, he is conversing with them on a series of ongoing hot topics of public discourses, such as religion-science dialogue, charity and the public good, and inner environmentalism and life ethics. Young university students affectionally regard him as “the Doctor of the Mind” and “the Scientist of Spirituality,” as he points out the pathology behind a whole range of the commonly felt states of the mind among modern Chinese , including depression, paranoia, anxiety disorder, alienation, affective disorder, to name a few. Coupling with his public lectures on university campuses, a series of his new books are entering the private collections of his young audience, e.g. Spiritual Remedies: the Only Cure for Mental Illness, Pure Land in the Human Realm, The Facts We Have to Face, and Receiving through Doing.

In midsummer 2012 before he headed to his youth summer camp hosted at the University of Hong Kong we met up in Shenzheng. Meeting him without the usually present crowds gave me an impression of him not so much of a leading Buddhist master but a precept-bound, traveling bhikkhu on a pilgrimage receiving teachings from one place to another. In his hotel room, his daily-used sutras are neatly wrapped in a maroon cloth and placed on the night stand along with his fountain pen and journal book. I saw books lying around on his bed and in his open suitcase. He is a monk, a writer, and a reader! The only “luxury” I saw (met) was his assistant monk who prepared tea and answered phone calls.

The next two days we spent together turned out to be his interview session with me. I was his “research subject.” He called his conversations with me “a drumming session,” meaning that everyone’s consciousness or state of being is like a drum. When it is not drummed it is silent; so he wanted to hear what I had to say about anthropology, religious studies, and human ecology – the three disciplines of social sciences that I’m familiar with. He was most inquisitive about social scientific research methods. I sensed from his questions and comments that his current intellectual interest is in articulating the Buddhist thought-system as a science of spirituality. He isn’t interested in aping modern science of European origin; instead he sees this science as a global consciousness with a religiosity of its own that is deeply engrained in social behaviors of countless individuals world over. China is an embodiment of such modern “scientific religiosity,” which operates like a matrix environing and saturating the whole being of the individual. In my social scientific mental association, this “scientific religiosity” resembles what Nancy Ammerman calls “everyday religion” (2007) or Meredith McGure “lived religion” (2008). Its canonic status is not questioned but lived and embodied. The core of Khenpo Sodargye’s science of spirituality does not deviate from Buddhism; however, its method of articulating human universals, e.g. pain, hope, and happiness, is actively absorbing modern scientific terminologies. Through critiquing and re-appropriating modern science, Khenpo Sodargye engages Chinese mainstream society with his own Buddhist science.

Subsequently we signed up with “Religion and Charity Conference” to present our first co-authored paper “Empathetic Giving and the Public Good: A Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Philanthropy in Practice.” The conference was organized by the Institute of World Religions at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences [CASS] in early December 2012. Khenpo Sodargye’s presence added dynamism to an otherwise slow academic conference. CASS directors and scholars were taking turns to have photos taken with him. A week after the conference CASS invited him back to give a talk titled “Exploring the Essence of an Inner Science.”

Toward the end of December we met again in Hangzhou. This time we had formal conversations on pre-agreed topics: “Potency of Tibetan Buddhism,” “Tibetan Buddhist modernity in contemporary China,” “Buddhist life ethics,” and “Tibet as an ecological reference for the environmental health of the Earth.” Since I’m also interested in an ethnographic consideration of his story, many of my questions tied the topics together with his spiritual turning points and existential gravity since his childhood. In the course of our conversation, he revealed touching moments including his recollection of Khenpo Depa who encouraged him to take discipleship with the late Khenpo Jigme Phuntsog, “A word of Khenpo Depa changed the course of my life…” he reflected with tears in his eyes, catching his assistant and me off guard and we scrambled for a box of tissues. The following day he gave a New Year address via live web broadcast to his Buddhist constituency scattered throughout China, Australia, North America, and Europe and he continued to express his affection toward the teachings he received from his past masters, “… when I reach the end of this life, [I will still consider] Buddha Dharma as always the rarest treasure I must seek…”

I look forward to identifying more of the turning points in Khenpo Sodargye’s life-story as I continue to work with him. In the meantime I’m contemplating his question – whether or not Buddhism needs validation from science since, according to him, it is a science in its own right.