Embrace. Dan Smyer Yu on film making

by Dan Smyer Yu

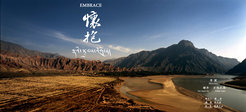

Embrace

Directors: Dan Smyer Yu and Pema Tashi

Producer: Dan Smyer Yu

Pre-production ethnographic work: Dan Smyer Yu

Film type: documentary

Length: 55 min.

Nominated for award at the First Beijing International Film Festival, 2011.

Synopsis

This documentary presents the complex reciprocal saturation of human communities, gods, Buddha Dharma, and natural landscape marked with religious significance. Through the narratives of a father and a son, this film illustrates both the transcendental and inter-sentient dimensions of Tibetan sacred sites and of their ecological significance. It documents a ritualized relationship of people and the place of their dwelling and natural surroundings. The juxtaposition of the cinematic narratives of the father and the son brings the audience a new sublime height of eco-spiritual reflections on the present and future states of our Planet Earth.

Embrace is my first professionally-intended film co-directed with Pema Tashi, a dear friend of mine. I also know his father well – everyone in Amdo [a Tibetan region] calls him Akha Parwa, a renowned radio broadcaster. His voice has resonated among Amdo Tibetans for at least four decades. I would not call our film a full visual anthropology project as both Tashi and I preferred to combine traditional documentary techniques and ethnographic filming. Tashi was trained at Beijing Film Academy specializing in documentary film directing. I have been doing still photography along with my fieldwork for the last decade. So, we put our talents together for the project. We called more film friends in. They are Sonthar Gyal and Dukar Tserang, two young Tibetan filmmakers who have worked for a decade with Pema Tseden – the first generation of Tibetan indie film director from Amdo, now based in Beijing. Google him, I’m sure you’ll see his film titles and a track record of multiple awards. So, all our crewmembers come from Amdo where I have done my ethnographic work for the last decade. We began our filming in spring 2010. It was the time when I was also revising my ![]() book manuscript for Routledge. Our footages of village events, ritual scenes, mountainous landscape, and interviews with the father and the son were so wonderful that I decided to write a new chapter on the eco-religious practices of Tibetans in Amdo. When the post-production of the film was finally completed in early 2011, we were exhausted but very satisfied. We submitted a 30-minute version to the Beijing International Film Festival in summer 2011. We were nominated for award. What was exceedingly rewarding was watching the film in a theatre, not for self-indulgent moments but for viewing the footages out of a digital cinema camera none of us had touched before –

book manuscript for Routledge. Our footages of village events, ritual scenes, mountainous landscape, and interviews with the father and the son were so wonderful that I decided to write a new chapter on the eco-religious practices of Tibetans in Amdo. When the post-production of the film was finally completed in early 2011, we were exhausted but very satisfied. We submitted a 30-minute version to the Beijing International Film Festival in summer 2011. We were nominated for award. What was exceedingly rewarding was watching the film in a theatre, not for self-indulgent moments but for viewing the footages out of a digital cinema camera none of us had touched before – ![]() RED One. I’ll get into the technical aspect of ethnographic filmmaking shortly. Stay tuned!

RED One. I’ll get into the technical aspect of ethnographic filmmaking shortly. Stay tuned!

But now, allow me to indulge myself in recollecting how this film was made. It was a certainly ethnographic film project, but it was also a new ethnographic opening to the world of contemporary Tibetan indie filmmakers. They truly invited me to experience the complex linkages of their rural homeland and urban professional lifestyle in Beijing, China’s “Hollywood.” Home is always being missed with a deep nostalgia but in the same time home is simultaneously the source of their creative inspiration and the ground of their cinematic representations of Tibetan culture, religion, and folk customs. Home is alive in its geographic location with their kith and kin, with monumental landmarks of sacred mountains, stupas in their villages, and with the ever-expanding modern highways cutting through the expansive landscape of their homeland. Home is also most definitely animated on screen in urban China, and in premieres and film festivals across the Western Hemisphere. Their cinematic productions were filmed in their homeland but the most of their audience members are not their folks but Tibetophilias in urban China, North America, and Europe. Their market niche is small but specialized enough to attract mostly graduate students, scholars, Buddhists, environmental activists, and those who have deep interest in the current state of affairs in Tibet.

While filming this documentary, Pema Tashi, my co-director, discussed with me several times how much he would like to send the film to festivals in Berlin, Amsterdam, Busan, New York, and other cosmopolitan centers. I understand his aspirations to establish himself as a young filmmaker in the film industry. My tight research schedule often didn’t permit me to spend time meticulously cutting a slick trailer and writing an attractive synopsis or a treatment. While we were in the field, I was more interested in showing this documentary on a village thrashing ground on a summer night to the folks I have worked with for the last decade. It would look like an American drive-in theater in the open except that everyone would bring their own chairs, stools, and cushions from their homes. I further imagined, the backside of the screen has to face the sacred mountain so that the mountain deity would have a chance to look at himself on the screen☺. Remember, in the film and my writing I emphasize that names of sacred mountains and mountain deities are the same in Tibet. This nomenclatural overlapping creates a perceptual conflation of the mountain with its deity: the mountain = the deity residing in it. The earth is then no longer an inorganic entity from this native perspective but is animated as an all-encompassing sentient being. I didn’t have the film shown on the thrashing ground but did give DVD copies to everyone in the film. Viewing the film with Aka Norbu’s family – father, mother, two brothers, and three sisters (one of them is deceased now) was full of touching moments. Aka Norbu’s two older brothers could not help but repeating the same sentence, “You’re the only one in the family doing the same thing as our father.”

Now the film is completed. What makes me think further about anthropological studies of identity, place, memory, and ecology is that memory is biographical, relational, and collective, and it clearly functions as the simultaneous presence of the past and the present. Like an ecological landscape, memory also possesses what James Gibson calls “affordances,” which are things-in-themselves but only materialize themselves in niched relations: a cave affords shelter for a family of wolves or snow leopards, and bamboos afford sustenance to pandas. Without the wolf or snow leopard families the affordance of the cave is present but is dormant. Likewise, the affordances of memory are indeed multiple but they come alive only when the memory is being recalled to the present in a particular context. It turns itself into history, into a reconstruction of the past, and into hope for the return of a gratifying past.