Blog | May 2020, The Sociological Review

Commodifying and Generating Spiritual Love: The Love Pilgrimage of Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi (1207-1273)

by Çiçek İlengiz

This blog was originally published on 30 April 2020 in The Sociological Review.

“[W]e come here to emanate love, to unify others and Him [Mevlana]. […] That’s what love means. But for locals, it’s all about money we spend here [in Konya]. […] They treat us as if we are customers, however, we’re in a love pilgrimage” [1] says one of the pilgrims to describe the shared unease among those coming to Konya to visit Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi’s tomb. Thousands of people following various spiritual trajectories, from all over the globe, come to Konya every year to participate in commemoration ceremonies and ecstatic rituals during the first two weeks of December. Culminating on December 17th, the Nuptial Night (Seb-i Aruz), also called the Wedding Night referring to Mevlana’s unification with God, the pilgrims claim to merge with his soul and energy through affectively charged rituals.

Known in neo-spiritual circles by his writings on spiritual love, Mevlana, the 13th century Persian Sufi thinker and poet, reached a broader audience after UNESCO’s celebration of his 800th anniversary in 2007. The experience of the love pilgrimage leads the production of an affective economy (Ahmed, 2009), and contextualization and historicization of affective ties illustrate that the experience of the love pilgrimage can hardly be analyzed independent from its conditions of possibility.

“When we are dead, seek not our tomb on Earth, but find it in the hearts of men of knowledge.” [2]

Although Mevlana wrote against the notion of monumental tombs, the visit to his shrine is at the heart of the love pilgrimage. Promoting connection with the dervish order, Mevlana’s teachings are famous for rendering questionable the mediation offered by sacred sites or figures between God and the believer and instead advocates transcending the borders between believers and the God suggesting to ‘unify in one’.

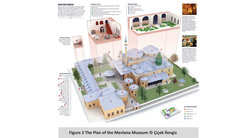

In Turkey, the plurality in mediation between the creator and the believer became also a concern for the Republican elite after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Considered the traces of the imperial legacies, sacred sites such as tombs of saints, dervish lodges and sites for traditional healing were closed down in 1925, soon after the establishment of the republic. However, the tomb of Mevlana, which was a part of a Mevlevi dervish lodge, has continued hosting its visitors almost without interruption; first it was transformed into the Konya Âsâr-ı Atika (Ancient Monuments) Museum in 1926 and into the Mevlana Museum in 1954 (see Figure 2).

One of the most visited tourist sites in Turkey, the Museum of Mevlana offers depictions of everyday life of dervishes including wide range of topics from education to music through textual and visual narratives.

Branding a City: “Konya, Şehr-i Aşk” / Konya, The City of Love [3]

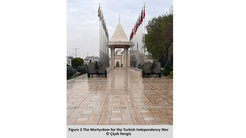

To participate the official commemoration ceremonies organized by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism one lingers between different cultural centers that are connected through Aslanlı Kışla Caddesi, the street of the “Lion Military Barracks”. Leaving the Mevlana Museum to watch the whirling dervish ceremony (sema) happening at the Mevlana Cultural Center one first needs to pass by the monumental Martyrdom Monument for the Turkish Independency War (see Figure 3) and the Panorama Museum where the official history of the Turkish Independency War is visualized with three dimensional techniques.

Konya started to be branded as ‘the city of love’ as a part of this bigger political and economic transformation happened in the post-1980 coup period. Following the military take-over in the 1980, which officially defined Islam as part of the integration keeping Turkish nation together against growing ethnic and religious tensions,[4] several traditions of dervish lodges that Konya has been hosting for centuries were revitalized. In addition, with the reckless implementation of neoliberal economic policies under the military rule, the middle-scale cities attracted unprecedented investment and marketing. Although Konya – and especially the tomb of Mevlana – has been spots for national and international spiritual tourism starting from the late 50s, the infrastructure allowing thousands of pilgrims to gather in the city started flourishing in the post-coup period. In other words, the conditions of love pilgrimage rendered possible through the offerings of a junta regime, which consolidated Islam as a part of Turkish identity and exhibit it creatively within the launching neoliberal market economy.

Upon reaching the Mevlana Cultural Centre, having been through a commercial district with lots of ‘Dervish-themed’ consumption opportunities, the pilgrims watch the official standardized sema ceremony (Figure 6) that is presented after a Turkish mystic music concert and a short talk on spiritual love given by theology professors. The tickets to the official sema ceremonies are usually sold out before the pilgrimage starts. As a part of the official love pilgrimage, in the first two weeks of December, whirling dervish ceremonies along with mystic music concerts, exhibitions, talks on spiritual love and Mevlana’s teachings take place in different parts of the city.

In these manifestations of the economy of spiritual love is at the centre of the love pilgrims’ motivations; they visit Konya for an authentic experience of receiving and generating spiritual love. This economy mobilizes different logics of capitalist production. Through exclusive focus on certain items and not others, and through turning spiritual love into artefacts, the love pilgrimage is suggestive of consumption generating and radiating spiritual love (Illouz, 2019).

However, the small streets behind the Mevlana Museum present a different picture of the ‘love pilgrimage’. Gathered in dervish lodges, hotel rooms and culture houses, love pilgrims whirl and participate in zikir rituals where they repeat enunciation of prayers leading to a state of trance. In contrast to well-scheduled and standardized picture offered in the official ceremonies, the self-organized gatherings present a diverse image in terms of clothing, gender relations and in ways in which rituals are performed (Figure 7).

Reaching a state of trance through repetition of prayers accompanied with bodily movement and whirling, the pilgrims who come together to commemorate theunificationof Mevlana with God, align with his energy. “While whirling in zikirs I clean myself from the constraints clinging to my body and liberate myself” says one of the female semazen and continues “[w]e come here to grow love, to reach our higher selves and to unify, become the one . That’s what love means for us. […] If the world would see the capacity of love that they inherit, there would be no wars as such today.” [5]

What we see in these lines suggests another economy, an affective one (Ahmed, 2004) that lines up bodies through the actual experience of the love pilgrimage. Spiritual love in this economy materializes a community of love composed of liberated bodies, elevated selves and enlightened subjects who are capable to imagine a world without wars. In contrast to the official structuring of the love pilgrimage – where the material heritage of Mevlana is spatially and discursively aligned with the national history that reifies itself through military failures and victories – here the community of love pilgrims invests into a political vision where people unify in peace.

Affective experience integrates the community, and despite attempts to distance authentic engagement from the official love pilgrimage, the affective economy of spiritual love is nonetheless deeply embedded into its conditions of possibilities that are materialized. In other words, the community of love has been cultivated within the infrastructure that is built by the official love pilgrimage. Thus, the authentic experience of spiritual love can hardly be separated from the process of its commodification.

-------------------------------

[1] Excerpt from the interview with a love pilgrim conducted in Konya, December 2019.

[2] The epitaph inscribed onto the tomb of Rumi.

[3] The opening sentence of the catalogue of the Museum of Rumi. Âşıklar Kâbesi: Ka’betü’l-Uşşâk: Mevlana Müzesi Kataloğu, (eds.) Hidayetoğlu, Selahaddin at all., Konya: Mevlana Kalkınma Ajansı, 2012.

[4] M. Hakan Yavuz, Islamic Polilical Identity in Turkey. (Religion and Global Politics) (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 69-70.

[5] Excerpt from an interview with a female semazen conducted in Konya, December 2019.