Blog | May 2020, Firstpost

A critical tribute to sociologist Yogendra Singh (1932-2020) — as a teacher, and his thoughts as a scholar

by Irfan Ahmad

This blog was originally published on 22 May 2020 in Firstpost.

This is the first ever tribute I pay to an admirable teacher whose classes I attended at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and who is no more: Yogendra Singh. In writing this tribute to my university teacher, I follow a lesson taught by my first teacher — my mother. I will conclude with that lesson.

***

An extraordinary teacher

It was heartening to see newspapers report about the death of Yogendra Singh, professor emeritus of sociology at JNU, who died on 10 May. Very few professors receive such media attention. Like our seniors, we, the students of the Master’s batch of 1994-1996, used to call him simply ‘Y Singh’. A towering figure, people across the board, especially the enthusiastic young lot, held him in high esteem, even awe. Ours was the last batch Singh taught before he retired.

There were many reasons for the kind of respect Singh enjoyed. He founded the department of sociology at JNU. Many teachers who taught us were themselves students of Singh and who too showed respect to him. Importantly, Singh’s persona was amiable. While my peers or I saw some teachers occasionally in unpleasant moods, Singh invariably wore a pleasant smile. Gifted with the impeccable art of communication, he was an excellent teacher. He never carried any notes to our classroom; yet, his lectures were far more coherent, intelligible and enjoyable than by those who did. While waiting for boring lectures by others to finish sooner, many of us wished Singh’s lectures were longer.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, the breadth of Singh’s knowledge was vast — beyond sociology. Urging us to be empirically grounded, his notion of reality, however, was markedly philosophical. Though not known for coining terms like MN Srinivas’ "Sanskritisation", Singh had unique skills to synthesise and connect. With a musical flow, in one class he connected Louis Dumont, Gunnar Myrdal, AK Saran, Romila Thapar and Leo Tolstoy. He also kept himself up-to-date with new knowledge in an age not yet of the internet. For a term paper I wrote for his course he directed me to read Ernest Gellner’s Postmodernism, Reason and Religion, published only two years earlier.

What struck me was that Singh also had an ironic streak that enabled him to laugh at himself. Once he narrated his experience of visiting a university abroad: Finding his writings difficult to understand, a colleague there gave him writing manuals. Having read them, Singh shared his new writing with that colleague who remarked, "This is more complicated than the earlier one". Right at that moment, Singh almost burst into laughter.

Leaving aside the issue of his difficult prose, I want readers to know troubling aspects of Singh’s thoughts as a scholar. This is critical to understand India’s political future no less than its present and past.

***

The ‘virus’ in Indian society

After his demise, Singh’s Modernisation of Indian Tradition (MOIT) was correctly described as ‘best selling’ and ‘sought-after among civil service aspirants,’ though calling it ‘path breaking’ and a ‘magnum opus’ is to go overboard. MOIT integrated the existing frameworks or arguments rather than make its own. This integration was remarkable. But MOIT was also unremarkable: an antagonism toward Islam and Muslims pervaded it. That it has not been spotted or publicly articulated is surprising.

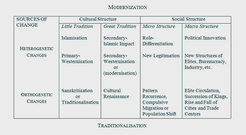

With its objective to explain ‘the causation of social change…both from within and without,’ MOIT treated Muslims as alien to India. Using the terms ‘orthogenetic’ and ‘heterogenetic’ for internal and external changes respectively, Singh branded Islam as heterogenetic. He presented his integrated paradigm, the book’s core, in a schema (see table below) where he portrayed Islam as an outsider. Importantly, Singh’s terminological choice was not innocent. In the Oxford English Dictionary, heterogenetic has two meanings. In philosophy, it means, ‘relating to external origination’. In medicine, it refers to disease, ‘infection from outside the body.’

By calling it heterogenetic, Singh thus cast Islam outside the body politic of India. Discussing the encounter between ‘indigenous and non-indigenous cultural tradition,’ he characterised Muslims as ‘colonisers and conquerors’. Singh also depicted Islam as exclusivist and intolerant: ‘The typical form that this holistic principle took in the Great Islamic tradition also influenced its character as an exclusive and assertive religion’ (originally published in 1972, quotes are from MOIT’s 1986 edition by Rawat, Jaipur, p. 25, 60, 63, 64).

Similar views also informed Singh’s other books. The last six pages of a chapter in Social Stratification and Change in India, published first in 1977, are subtitled ‘Social Stratification among non-Hindu Communities.’ There is no subtitle in the first 32 pages where India is assumed throughout to be Hindu.

***

Responsibility between power and knowledge

Without multiplying examples, let me make it clear that Singh was not the only sociologist to uphold such a perspective. Shyama Charan Dube (d.1996) held similar views. In Indian Society, published in 1990 by National Book Trust (p. 27), which, like Singh’s MOIT was an indispensable book to aspiring civil servants, he described Muslims as ‘Islamic invaders.’ He devoted six pages to this invasion and not even one page to colonialism by the British who just ‘came to India.’ Iravati Karve (d. 1970), regarded as the first woman sociologist of India, also depicted, as did Singh, Muslims as external and inimical as follows: ‘The Mohammedans have been in India for about a thousand years. They created the first breach in the cultural unity of India. …They have left terror and destruction in their wake’ (Racial Problems in Indiapublished by Indian Council of World Affairs, Delhi, 1947, pp. 45–46).

There is more than a correspondence between contemporary politics and sociological knowledge such as Singh’s. Consider two examples. First, a recent report documents how many police officials think that Muslims are ‘naturally prone towards committing crime.’ It is reasonable to say that they became police officers reading, among others, such books of sociology. Second, right on the floor of India’s parliament, in 2014 the new Prime Minister spoke of ‘1200 years of servitude.’

While studying sociology at JNU was exciting, reading books like Singh’s was also intimidating and alienating. Sociologists love to talk about alienation in society. However, discussing alienation sociologists themselves unleash is tabooed. By breaking this taboo, I probably make myself vulnerable. But initiatives that seek liberation from boredom of dehumanising, nationalising orthodoxy entail vulnerability.

This critical tribute to Prof Singh echoes the lesson my late mother taught: Relate of the dead only that which is good, and refrain from speaking ill of them. It also echoes, so I hope, the lesson in constructive critical thinking that Singh taught us.