Teaching Virtual Interreligious Ethnography in a Pandemic

by Samuel Sami Everett

Blog | February 2022

Experiences taken from the following University seminars:

- Digital Interreligious Encounters in Urban Contexts (DIEU.X) — CDH, University of Cambridge 2020-21

- Ethnographie du religieux — Université de Strasbourg 2021-22

Teaching ethnographic methods – that is, how to prepare, think through, take notes, interview (and if and when this might be necessary), reflect and write up research fieldwork – is a demanding and sensitive business. When this is coupled with the need to teach about inter religious contact and in particular encounters — real or imagined — between Muslims and Jews, it becomes even more delicate. Throw in a global pandemic and serious restrictions to movement and reaching out in person and you’ll have an idea of why I have been developing such a class first for research students and researchers at the University of Cambridge (2020-21) and then for research students at the University of Strasbourg (2021-22)*.

Before we initiated the Encounters project and when we were in the throes of responding to our funders concerning the logistics of such a wide-scale ethnographically-led research project across six cities — Berlin, Frankfurt, London, Manchester, Paris and Strasbourg — we considered carefully the implications of the shift online that has accompanied the pandemic. It would require we thought three interconnecting strands of methodological and pedagogical engagement: adaptation (virtual/in-person); diversification (of data — media, attitudes, non-academic literature) and exchange — sharing these experiences. The two classes that I developed and taught took up all of these ideas in tandem with researchers associated with the project:

- Adaptability — the different degrees of mobility and thresholds to viral risk have meant being able to start and stop in-person ethnography. This means at once being ready to undertake anew fieldwork that was on hold and to be prepared, i.e. sufficiently organised, to start work on new sites with interlocutors who you have not yet met, at short notice. Meanwhile desktop research has become de rigueur. For many ethnographically inclined researchers this presents a golden opportunity to simultaneously read and write up notes and experiences. In his contribution to the seminar, Ben Kasstan was able to formulate with great sensitivity both the precarity of the position of the ethnographer who needs to improvise with digital tools in this new context such as on-line questionnaires, visioconference tech, chat recording etc. (what we might term “methodological precarity”) and the particular focus on Orthodox religious communities (both Jewish and Muslim) as the 'bad citizen' during the pandemic — still meeting, vaccine-reticent and hence undermining the immunity of the nation state — within the context of his work on healthcare and haredi Jews.

-

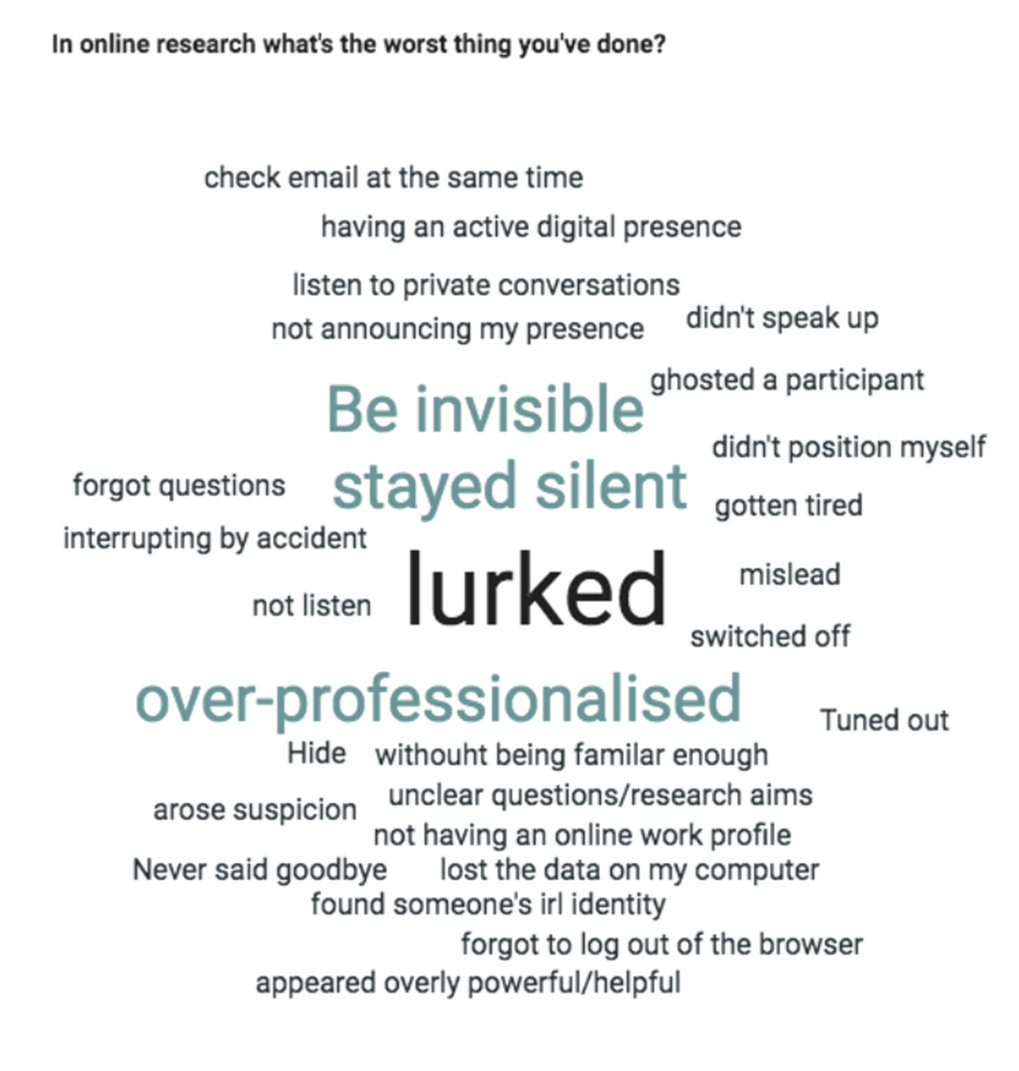

Diversification — everyday online sources and in particular community media can bolster and be used as a further layer of ethnographic detail, i.e. what are people reading or watching/listening to, but also as a point of engagement with interlocutors. Dr Hanane Karimi’s guest talk focused on the ethics of online fora such as the Facebook comment function but also online magazines with regard to the representation of hijab-wearing Muslim women in France and the dynamics of associated images to a particular group (example of Dr Karimi’s work here). Prior to this talk we considered the effect of online anonymity via an online exercise: I invited the class to contribute to an anonymous virtual chat room. Star academics Prof Nonna Mayer and Vincent Tiberj, whose manuscript in preparation on Sarcelles introduced the class to conducting surveys by phone and online and the degree to which it was possible to achieve nuanced data with such methods, data on attitudes which can in turn help to articulate themes for ethnographic work. To prepare this class we took part in an online wordcloud application.

Diversification — everyday online sources and in particular community media can bolster and be used as a further layer of ethnographic detail, i.e. what are people reading or watching/listening to, but also as a point of engagement with interlocutors. Dr Hanane Karimi’s guest talk focused on the ethics of online fora such as the Facebook comment function but also online magazines with regard to the representation of hijab-wearing Muslim women in France and the dynamics of associated images to a particular group (example of Dr Karimi’s work here). Prior to this talk we considered the effect of online anonymity via an online exercise: I invited the class to contribute to an anonymous virtual chat room. Star academics Prof Nonna Mayer and Vincent Tiberj, whose manuscript in preparation on Sarcelles introduced the class to conducting surveys by phone and online and the degree to which it was possible to achieve nuanced data with such methods, data on attitudes which can in turn help to articulate themes for ethnographic work. To prepare this class we took part in an online wordcloud application.

-

Exchange — multiple opportunities to discuss our own work as early career researchers were built into the classes via break-out discussion rooms to which I was able to ‘drop-in’. This contributed to the construction of a space in which participants felt at ease to contribute to discussion and less vulnerable. Indeed the notion of failing to understand and the ethnographic progress this can entail emerged as a key theme from these discussions (see this blog post). This enabled a dynamic exchange in which the fragility of failure was not immediately interpreted normatively as a missed opportunity but rather was allowed to remain hanging as a question mark or indeed a pedagogical or methodological experience on which to draw.

Exchange — multiple opportunities to discuss our own work as early career researchers were built into the classes via break-out discussion rooms to which I was able to ‘drop-in’. This contributed to the construction of a space in which participants felt at ease to contribute to discussion and less vulnerable. Indeed the notion of failing to understand and the ethnographic progress this can entail emerged as a key theme from these discussions (see this blog post). This enabled a dynamic exchange in which the fragility of failure was not immediately interpreted normatively as a missed opportunity but rather was allowed to remain hanging as a question mark or indeed a pedagogical or methodological experience on which to draw.

Each of these strands of engagement are areas in which the Encounters project is seeking to better integrate the virtual into the ethnographic to allow for knowledge exchange to emerging research students and early career researchers. This exchange includes issues of methodological precarity i.e. having to adapt at short notice and utilise tools with which we are not familiar, the opening up of new ethnographic practices (for example with ubiquitous online tools such as Zoom, Slido, anonymous chatrooms or social media) and the necessity to share and discuss the context-based challenges we face as researchers without judgement.

Samuel Sami Everett — Research Coordinator, ENCOUNTERS

*Next year this seminar series will be based in a German University.

** Later this year I will write another blog entry on the in-person meeting with the Rabbi of a underprivileged neighbourhood in Strasbourg taken from the second half of what was a hybrid seminar (half online and half in-person) at l’Université de Strasbourg