Exploring Frankfurt’s Deep-Story and Impact on Jewish-Muslim Encounters

by Arndt Emmerich

As a sociologist and urban ethnographer for the research project ENCOUNTERS, I investigate historical and contemporary interactions and understandings of Jews and Muslims in Frankfurt. To explore what the American sociologist, Ariel Hochschild, called the deep-story that shapes how people think, feel, behave and relate to each other. I am looking at the field of engineered encounters–in particular interreligious dialogue–where identity markers (such as Jewish or Muslim) play a prominent role. In parallel, I am looking at the area of informal or un-staged encounters such as mundane and free-flowing interpersonal and transactional relations at the neighbourhood level where boundaries are described as soft or are deliberately down-played. Both are intriguing areas, potentially adding analytical value to the project and a specific Frankfurt-based contribution.

Frankfurt’s is known for its prominent banking sector with its mighty skyline, its football club, Eintracht Frankfurt, the Goethe University and the important legacy of the Frankfurt School. The city has more than 80,000 Muslims (and over 50 mosques), likely the highest percentage in Germany (proportional to the small city population of 750.000). Frankfurt has also one of the highest Muslim migrant representations in the city parliament (Magistrat) and other city council representative bodies among German cities. This development is co-related to the foundation of the eminent Department of Multicultural Affairs (Amt für multikulturelle Angelegenheiten, in short: AMKA) in 1989, which was founded by the French-German, secular Jewish Green Party politician Daniel Cohn-Bendit. AMKA in cooperation with the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity was the first of its kind to adopt the concept of super-diversity in its integration, interreligious, and intercultural governance.

Frankfurt is also at times referred to as the “the most Jewish city” (“jüdischste Stadt”) in contemporary Germany and has the first and only Jewish mayor (Oberbürgermeistern) since the Shoa, who was until recently married to a Muslim woman. Before the Shoa, Frankfurt was one of the world’s leading centres for Jewish culture and theology.

Between 6400 and 7000 Jews reside in Frankfurt today. The city has been deeply influenced by Jewish institutions and politicians across party divides at the forefront of various key protests around Jewish identity in post-WW2 Germany, calling out antisemitism and speaking up for other especially Muslim minorities in the context of increasing neo-nazi attacks in the early 1990s. For ENCOUNTERS a broader research question has hence emerged: How does Frankfurt’s deep story and urban narrative around conviviality impact Jewish- Muslim encounters (for which I’ll now introduce two vignettes of formal and informal encounters)?

Engineered Encounters and Interfaith Activism

Frankfurt has produced several important interfaith initiatives such as an interreligious choir, an Abrahamic Forum, the Hessian Forum for Religion and Society, a recently launched LGBTQI+ inclusive interfaith network as well as interreligious collaborations at the neighbourhood (Stadtteil) level (e.g. Interreligiöse Forum Bahnhofsviertel).

The most prominent initiative is Frankfurt’s Council of Faiths (Rat der Religionen) inspired by the Leicester Council of Faiths in England which was founded in 2009 . The Council consists of 9 religious communities and 23 members. Its main objective is to mediate and prevent interreligious tension and is thus seen by the mayor and city council as the key broker for the governance of the religious diversity in the city. It has won several awards such as the prestigious Frankfurter Integrationspreis in 2012 and the Hessian Integrationpreis in 2019. In this way, Frankfurt’s Council of Faiths mirrors a wider trend within Germany’s national integration policy and the governance of religious diversity, in which interfaith councils and interreligious dialogue initiatives as fora for local peace have flourished and multiplied. There is a growing academic literature and research field within the sociology of religion, religious and migration studies and political sociology – focusing on interfaith relations and how they can be managed.

Through the case study of Frankfurt’s Council of Faiths and other at times competing initiatives, I contextualize and investigate how Jewish Muslims relations are negotiated, disrupted and re-established. Perceived by policy-makers as a prime institutions to ensure social cohesion, I show that such initiatives can also become involved in internal and external disputes and political crisis, in particular over Jewish-Muslim relations and (extra-)local events (e.g. occurrences in the Middle East). In researching such organized interfaith encounters, I have become interested in how crisis moments lead to new management strategies and processes of institutionalization, changing internal affairs within Muslim, Jewish and other faith communities and altering partner choices within dialogue constellations. My research is therefore contributing to the academic field of interfaith dialogue and the governance of religious diversity. This field mainly focuses on the local accommodation of religious minorities (especially Muslims) and wider dynamics within interreligious settings, while an explicit emphasis on Jewish-Muslim relations is still lacking, but could potentially yield new insights into interfaith governance.

Frankfurt’s Central Station Area (Bahnhofsviertel)

The second part of my ongoing research is on so-called un-staged or informal encounters. One of the neighbourhoods that I observe is the Frankfurter Bahnhofsviertel. Its dynamism and diversity is manifested in the geographical size and demography as the second smallest neighbourhood in Frankfurt with 3552 residents (2019) of whom 65% have migrant biographies. In the 1950s and 1960s, Jewish displaced persons (DPs) from Poland and other Eastern European countries, who were stranded in Frankfurt on their way to Israel or the US, started business endeavours in the Bahnhofsviertel, while slowly re-building Jewish life in Germany. The author Michel Bergmann who grew up there, wrote about Yiddish life in the Bahnhofsviertel in the 1950s in his autobiographic novel Machloikes.

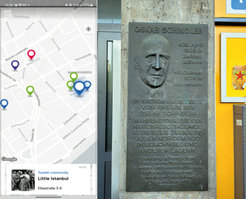

Close to the central station is a small memorial sign on a tall building, which is dedicated to Oskar Schindler, who lived in the Bahnhofsviertel for 17 years. His apartment was bought by the Jewish community as he had limited financial resources in the post-war era. The ongoing public debate regarding the creation of a “Schindler Square” in front of the central station is a very interesting case study, revealing tension over Germany’s contested memory culture and grassroots criticism of such an “elite” project far away from the life worlds of those who usually inhabit the space.

The Bahnhofsviertel was also shaped by the arrival of Muslim labour migrants from the 1970s onwards, who, through steady investment, contributed to the uplift of the neighbourhood. Parts of the neighbourhood today can be described largely as a Muslim ethnic economy with shops, restaurants and mosques. In May 2022, I took part in the annual iftar (breaking of the fast) celebration in the Bahnhofsviertel, which is organized by a local trade association in cooperation with a local Turkish mosque. The event is attended by the mayor and is financially supported by Jewish business owners in the area. In the same space is a bakery which sells kosher bread (certified by the rabbi of the Westend synagogue), and a few Jewish-owned shops, while the new Jewish Museum in the Rothschild Palais is around the corner. Due to ongoing gentrification over the past 15 years, restaurants, bars and small music scenes have been emerging in the area some of which are Jewish and Muslim-owned.

Despite many contrasting life worlds, the Bahnhofsviertel with its own deep story generates unique formulas of local peace, which has implications for the study of Jewish-Muslim encounters. Through long-term ethnographic engagement, I therefore explore the daily encounters that make up Jewish and Muslim life, tracing the historical legacies of the Shoa and contemporary political, cultural and religious expressions in their daily manifestations in these spaces. In doing so, the research sheds light on how urban locations, institutions, initiatives and friendships, in which Jewish-Muslim encounters take place, are constructed and re-imagined by politicians, creative marketing agencies, trade associations, ethnic entrepreneurs, and cultural and religious influencers as spaces and projects of conviviality but also the conflictual dynamics that emerge through these efforts.