"Vigilant Ethnicity: Korean Chinese Communist Party Members Encounter the Forbidden Homeland"

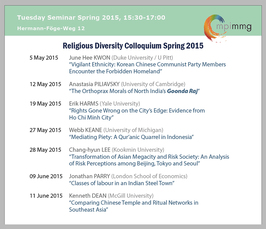

Religious Diversity Colloquium Spring 2015

- Datum: 05.05.2015

- Uhrzeit: 15:30 - 17:00

- Vortragende: June Hee Kwon (Duke University / U Pitt)

- June Hee Kwon is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Anthropology/University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. She will join the Department of East Asian Studies at New York University as Assistant Professor/Faculty Fellow from September 1, 2015. She received her Ph.D. from the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University in 2013. Her research and teaching focus on transnational migration and human rights, kinship and ethnicity, and affect and economy. Her area of expertise spans contemporary Korea (North and South) and China, and includes postcolonial and post-Cold War East Asian inter-connections. She was a recipient of the Eric Wolf Prize by the Society of Anthropology of Work, and the Sylvia Forman Prize by the Association of Feminist Anthropology. Her article, “The Work of Waiting: Love and Money in Korean Chinese Transnational Migration,” appears in Cultural Anthropology 30:2 (May 2015).

- Ort: MPI-MMG, Hermann-Föge-Weg 12, Göttingen

- Raum: Conference Room

For more details please contact vdvoffice(at)mmg.mpg.de.

Since China and South Korea normalized diplomatic relations in 1992, Korean Chinese, part of an officially recognized ethnic minority group in China, have migrated to Korea in search of both long-lost family members and better working opportunities. This massive and persistent migration to Korea is commonly called the Korean Wind. Based on ethnographic research in Yanbian, China, this paper examines how the ethnic politics of Korean Chinese Communist Party members have developed in response to the Korean Wind. South Korea was long been considered a forbidden capitalist enemy. How have these party members re-conceptualized their ties to South Korea, a relationship that was used as grounds for political persecution during the Cultural Revolution? How have they dealt with the economic affluence and cultural changes brought about by the Korean Wind over the last two decades? The elderly party members I interviewed exemplify a sharp split in the politics of ethnicity that distinguishes economic intention from political position—they are highly economized by the transnational migration to Korea while at the same time intensely politicized because of their tight identification with China as socialist subjects. I argue that the combination of economic need with a sense of multiple belonging is what constitutes and generates Korean Chinese as a vigilant ethnicity. This paper details the emergence of “Yanbian socialism,” a political nexus articulated between post- Cold War circumstances, post-socialist China, and neoliberal East Asia.