"Rights Gone Wrong on the City’s Edge: Evidence from Ho Chi Minh City"

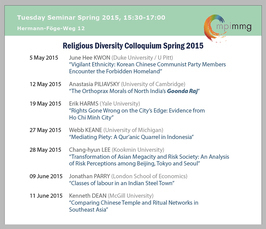

Religious Diversity Colloquium Spring 2015

- Datum: 19.05.2015

- Uhrzeit: 15:30 - 17:00

- Vortragender: Erik Harms (Yale University)

- Erik Harms is an Associate Professor of Anthropology and International & Area Studies at Yale University, specializing in urban anthropology, Southeast Asia, and Vietnam. His ethnographic research in Vietnam has focused on the social and cultural effects of rapid urbanization on the fringes of Saigon—Ho Chi Minh City. His book, Saigon’s Edge: On the Margins of Ho Chi Minh City (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), explores how the production of symbolic and material space intersects with Vietnamese concepts of social space, rural-urban relations, and notions of “inside” and “outside.” He has published articles in Cultural Anthropology, American Ethnologist, City & Society, Pacific Affairs, Positions, and is the co-editor of Figures of Southeast Asian Modernity (Hawaii, 2013). Harms is currently writing a book about the demolition and reconstruction of the urban landscape in two of Ho Chi Minh City’s New Urban Zones, Phu My Hung and Thu Thiem. Please visit his project website for more information on this research: http://newurbanvietnam.commons.yale.edu/.

- Ort: MPI-MMG, Hermann-Föge-Weg 12, Göttingen

- Raum: Conference Room

For more details please contact vdvoffice(at)mmg.mpg.de.

This paper is based on a chapter in progress from a new book I am writing about master-planned periurban developments in Ho Chi Minh City. The paper focuses on residents who have been evicted in order to make way for a new urban development and how they have increasingly mobilized a language of “rights” to support their cause. In some ways, their examples show the ways in which this emerging “rights consciousness” can inspire new forms of agency and collective action. But the paper also describes the ways in which these rights also operate as something of a fetish. For in the final assessment, the evictees’ focus on property value, legal documents, petitions, and other artefacts central to bureaucratic rights has led to a proliferation of abstract rights that are not in fact realized in practice. After the dust settled and the bulldozers retreated, these residents found themselves dispossessed from house and home at precisely the moment that they had so forcefully managed to understand themselves as rights-bearing subjects. This suggests that the new conception of rights emerging on the edges of Vietnamese cities cannot be disentangled from the very processes fueling dispossession.