Two exhibitions on Muslim-Jewish relations in Paris: finding what to show

by Elodie Druez

Blog | August 2022

By happy coincidence, two major exhibitions on Muslim-Jewish relations have taken place over the course of the Parisian fieldwork of the Encounters project that I am in charge of. The first, called Juifs d’Orient (Jews of the Orient) curated by Elodie Bouffard and Benjamin Stora, took place at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA, Arab World Institute) from November 2021 to March 2022. It aimed to explain the long history of the Jewish presence in the Middle East and North African region. The second, Juifs et Musulmans (Jews and Muslims), centred in on relations between Muslims and Jews from colonial France to the present day in the Maghreb and in France. Curated by Karima Dirèche, Mathias Dreyfuss and Benjamin Stora, it opened in April 2022 at the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration (MHI, Museum of the History of Immigration) also known as the Palais de la porte dorée, and has just come to an end. These two exhibitions – for which Benjamin Stora, a historian and specialist of the history of Algeria, was the initiator – demonstrate a desire to improve public understanding of these histories and to take a step back from contemporary polemics. This is for two reasons: on the one hand, relations between Jews and Muslims in France have, over the last two decades, been presented as increasingly tense, and on the other, the generation of Muslim and Jewish émigrés from the Maghreb in the 1950s and 1960s is getting older, awakening awareness of the need for remembrance. These two exhibitions are in dialogue with one another and were conceived in continuity the one with the other: Malika Ziane, general assistant for the Juifs et Musulmans exhibition, used for instance the first to introduce the visit of the second to a group of students (that I attended).

These exhibitions raise a whole series of questions that the curators asked themselves and that we are analysing in the context of the Encounters project: How can we put into narrative form and historicise such burning issues? What angle, what pieces of work, what terminology should be chosen to talk about these complex and tempestuous histories?

These exhibitions aimed at developing a scientific discourse based on facts that reveal the plurality of these relations in a nuanced way. However, they faced the difficulty of putting into images a political history, marked by relationships of domination, inequalities of treatment and by the political manoeuvring of nation-states. How to illustrate for instance the French administration’s deliberate instigation of tensions between Muslims and Jews in its Maghrebi colonies? In both cases, the objects and documents that it was possible to obtain and exhibit led the curators to focus on certain aspects rather than others.

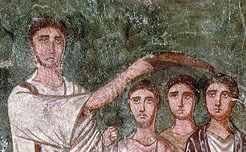

Each exhibition faced radically different challenges, especially in terms of their design. The Juifs d’Orient exhibition was given a traditional format which build a historical narrative around objects and artworks borrowed from museums around the world: liturgical, traditional clothing, books, paintings, photos. The Juifs et Musulmans exhibition was confronted with a lack of objects to illustrate Muslim-Jewish relations in the colonial context. Senior exhibition curator Mathias Dreyfuss told us[1] in an interview that no museum had a “Jewish-Muslim relations” category to classify the objects in their collection, the issue having been hitherto entirely ignored. The Juifs et Musulmans exhibition is thus particularly centred around archives, especially colonial administrative archives.

For Juifs d’Orient, the exhibition is marked by a Moroccan prism, as Moroccan partners made a significant number of objects available. Conversely, at the MNHI, Algeria was given the main stage. This is due to the profusion of colonial archives produced by the French administration in Algeria – considered a part of France (not a protectorate) – which were much less in the protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco.

These two examples suggest how museum narration is limited in its possibilities, constructed not only around what curators wish to say but also around what one can tangibly show to visitors. Topics that are non-material, that were not considered important enough to be documented in the past, histories that are painful or taboo are thus difficult to convey in the context of an exhibition. This was the case, for the Jews of Algeria in the exhibition Juifs d‘Orient or for the lives and trajectories of women in the exhibition Juifs et Musulmans. The latter exhibition has furthermore been criticised for not giving enough place to a Muslim perspective: the curators explained, during a conference held at the Museum, their difficulty in finding Muslim North African sources. However, this led to much less controversy than the Juifs d’Orient exhibition, which was widely attacked for having borrowed works from Israeli museums. Israel/Palestine remains visibly the most acute subject of tension in Muslim and Jewish relations in France.

[1] I conducted the interview with Samia Hathroubi, PhD Candidate at the University of Heidelberg.